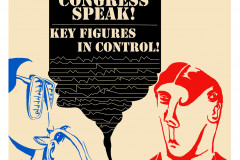

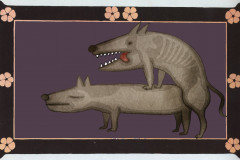

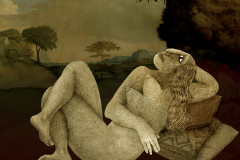

Spoerri, Daniel (1930-): Zuhany, 1961 (olaj, vászon, zuhanyzó, 70,2 x 96,8 x 18,5 cm, Musée national d'art moderne – Centre Pompidou, Párizs). A román származású svájci művész mind a mai napig az egyik legkövetkezetesebb és legkreatívabb képviselője az '50-es években indult Nouveau Réalisme (Új Realizmus) mozgalmának. Munkáiban folyamatosan a valóság és művészet viszonyát kutatja. Pl. a Zuhany c. asszamblázsban: vajon kifolyik-e a festett víz, ha megnyitjuk a csapot? A Ruben Brandtban a tokiói pop-art-kiállításon látjuk a művet egy fürdőkádas installáció társaságában.

Egy kis elmélet: Spoerri „détrompe-l'oeil”-nek (azaz nehézkesen fordítva a „szem nem-becsapásának”) nevezte azon munkáinak sorozatát, ahol realisztikus igénnyel fellépő, a valóság illúzióját keltő műalkotásokat kombinált valódi tárgyakkal, így hívva fel arra a figyelmet, hogy egy művészi ábrázolás – legyen az bármilyen valószerű – soha nem tűnik valóságnak a valóság mellett. A „trompe-l'oeil”-nek, a „szem becsapásá”-nak az európai festészetben az ókori görögök óta óriási hagyománya van, Spoerri szerint ő az utolsó művész, aki csatlakozik a sorba. Ócskapiacokon, padlásokon kutat fel realisztikus műalkotásokat, mint pl. a hegyi folyócskát sebesen felénk zubogva ábrázoló tájképet, s helyez rájuk egy témában passzoló mai tárgyat. A folyó így egy zuhanyzó csaptelepébe torkollik, azt az illúziót keltve, hogy ha megnyitjuk a csapot, a víz máris kifolyik rajta, a kép világa egyszerűen átömlik a fürdőszobánkba. Csakhogy ezt az „illúziót” senki sem hiszi el. Ha egy tárgyat teszünk a képre, a festmény is rögtön csak egy tárggyá válik, s nem is értjük hirtelen, hogyan hihettünk eddig mást? A film-beli pop-art-kiállításon aztán bőven látunk példát arra, hogy a műalkotásokat csak „tárgyi minőségükben” kezelik: dobják, pörgetik, rúgják, szakítják őket – na nem feltétlenül művészetelméleti megfontolásokból.

Spoerri, Daniel (1930–): Shower, 1961

(oil on canvas, shower fixture, 70.2 × 96.8 × 18.5 cm, Musée national d'art moderne – Centre Pompidou, Paris)

Daniel Spoerri, a Romanian-born Swiss artist and one of the key figures of the Nouveau Réalisme (New Realism) movement, has long explored the fluid boundary between art and reality. In Shower, an assemblage piece mixing oil painting with a real bathroom fixture, he poses a deceptively simple but unsettling question: If you turn the tap, will the painted water flow? In Ruben Brandt, Collector, this thought-provoking work appears at the Tokyo pop-art exhibition, installed alongside a full bathtub display—where the surreal logic of Spoerri’s art seems to come to life.

Spoerri coined the term détrompe-l’œil—literally “un-deceiving the eye”—to describe works that expose the limits of visual illusion. As a witty reversal of the classical trompe-l’œil tradition, where painting aims to mimic reality so convincingly that it tricks the viewer’s perception, Spoerri’s pieces combine painted illusions with real, three-dimensional objects. The effect is jarring: far from enhancing the illusion, the intrusion of an actual object collapses it.

In Shower, a realistic painting of a mountain stream—perhaps scavenged from a flea market—is altered by the addition of a real faucet, mounted where the stream narrows and rushes toward the viewer. The implication is absurd and magical: turn the tap, and the river might spill into your sink or tub. But, of course, it doesn’t. The presence of the object doesn't complete the illusion—it destroys it. The painted stream becomes only paint again, and we are reminded of how willingly we suspend disbelief in the face of skilled representation. Once a "thing" enters the frame, the image can no longer masquerade as nature.

This ironic dismantling of illusion mirrors the visual logic in Ruben Brandt, Collector. The film, like Spoerri’s assemblage, is full of moments where images break their boundaries—stepping out of frames, chasing the viewer, falling apart or becoming real. Paintings are thrown, torn, handled like physical objects. But this isn’t just slapstick: it reinforces a core question about perception. When does art stop being image and start being object? What do we lose—and gain—when we touch what we once only looked at?

Spoerri’s Shower isn’t just humorous or conceptual—it’s also an invitation to think critically. And maybe, to laugh a little while doing so.