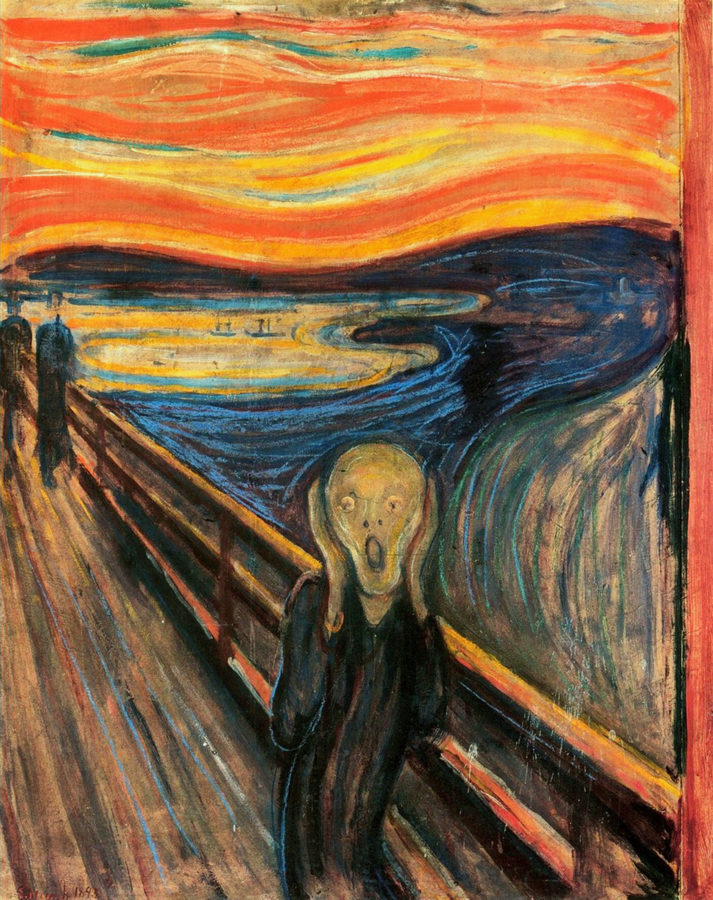

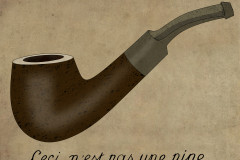

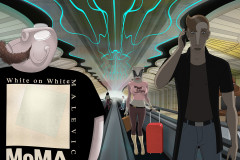

Munch, Edvard (1863-1944): Sikoly, 1893 (tempera, olaj, pasztell, kartonlap, 91 x 73,5 cm, Oslo, Nasjonalmuseet). Az expresszionizmus és szimbolizmus képviselőjeként számon tartott norvég festő 1893 és 1910 között négy festményt és egy litográfiát készített a témáról, amely az európai festészet egyik leghíresebb motívuma lett. A filmben a párizsi üldözéses jelenetben a hídon átszáguldó autóktól rémülten sikoltó nő alakjában ismehetünk a Munch-képre, a fekete-fehér litográfia-változat pedig Ruben Brandt pólóján tűnik fel a Psychology Journal címlapján.

Mint egy látomás, olyan megfoghatatlan és erőteljes Munch Sikolya, amely annyira beleivódott az európai kultúrába, hogy szinte bárki fel tudja idézni a hídon álló, koponyaszerűvé torzult fejét fogó, kétségbeesetten sikító alakot. A világhírű performance-művész, Marina Abramovic 2013-ban „életre is keltette” a festményt, azaz először ő, majd oslói emberek állhattak kamera elé a kép feltételezett készülési helyén egy képkerettel a kezükben, s szakadhatott ki belőlük saját személyes sikolyuk. Mintha igény lenne erre, hogy a modern ember szorongása, frusztrációja, rettegése és még ki tudja mennyi érzelme egy ilyen artikulálatlan formát ölthessen. Bármennyire félelmetes, úgy tűnik, könnyű azonosulnunk a képpel. Pedig Munch valójában a „Természet sikolyának” nevezte el festménysorozatát, s egy naplóbejegyzésében meg is indokolja ezt: „Egy este épp egy gyalogúton sétáltam, amikor a város az egyik oldalon volt, míg a fjord alatta. Fáradtnak és betegnek éreztem magam. Megálltam és elnéztem a fjord fölött, – a Nap éppen lemenőben volt, amikor az ég vérvörössé változott. Úgy éreztem, hogy egy sikoly préselődik ki a tájból és úgy tűnt számomra, mintha hallanám a sikoltást. Megfestettem a képet és a vérvörös felhőket. A színek szinte sikoltottak. Ez vált A sikollyá.” Ez az alkotási mód pedig az expresszionizmus – amikor az alkotó érzései, érzetei alakítják a motívumot, áthatják az egész ábrázolást. A kép a műkincsrablók körében is népszerű – többször is ellopták az oslói múzeumból, 1994-ben pl. pont a Ruben Brandt kliensei által is művelt „képkivágós” módszerrel.

Munch, Edvard (1863–1944): The Scream, 1893 (tempera, oil, pastel on cardboard, 91 x 73.5 cm, Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo). As a representative of Expressionism and Symbolism, the Norwegian painter created four painted versions and one lithograph of this subject between 1893 and 1910—making it one of the most iconic images in European art. In Ruben Brandt, Collector, the painting is evoked in the figure of a terrified, screaming woman on the bridge during the Paris chase scene, while the black-and-white lithograph version appears on Ruben Brandt’s T-shirt, featured on the cover of Psychology Journal.

Like a vision, The Scream is both elusive and intensely powerful—so deeply embedded in European culture that nearly anyone can conjure the image of the skeletal-headed figure clutching its face in despair on a bridge. In 2013, world-famous performance artist Marina Abramović “brought the painting to life” when she and later Oslo residents stepped in front of a camera with a picture frame in hand at the supposed location of the painting’s setting—each releasing their own personal scream. The act suggests a collective need for modern humans to give shape to their anxiety, frustration, and fear in such an inarticulate form. As unsettling as it may be, the image seems strangely easy to identify with.

Yet Munch originally titled the series The Scream of Nature, and explained its origin in a diary entry: “One evening I was walking along a path, the city on one side, the fjord below. I felt tired and ill. I stopped and looked out over the fjord—the sun was setting, and the sky turned blood red. I felt a scream pass through nature; it seemed to me I could hear the scream. I painted this picture—the clouds were like actual blood. The colors were screaming. This became The Scream.” This method of creation is the essence of Expressionism, where the artist’s feelings and perceptions shape and saturate the entire image.

The Scream has also been popular among art thieves—it was stolen multiple times from the Oslo museum, including in 1994 using a “cut-out technique” not unlike that favored by the clients of Ruben Brandt.