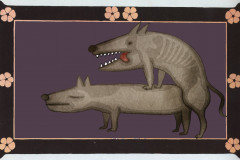

Friedrich, Caspar David (1774-1840): Két férfi nézi a Holdat, 1819-20 (olaj, vászon, 33 x 44,5 cm) Galerie Neue Meister, Drezda. A német romantika tájképfestészetének egyik legismertebb alkotása a korszak emblematikus művévé vált, hiszen minden megtalálható rajta, ami a romantikára jellemző: éjszakai hangulat, a sejtelmes fényű Hold, látványos természeti elemek és a köztük rejtőzködő ember. A filmben Ruben Brandt a Piroska és a farkas pszicodramatikus feldolgozását végzi pácienseivel a Friedrich-képet idéző erdei tisztáson.

A friedrichi táj kiválóan alkalmas a belső, lelki munkára, hiszen a festő maga is belső képeiből dolgozott. Annak ellenére, hogy számos tanulmányrajzot készített a számára oly kedves és egyedül érdekes északi tájról, mégis vallotta: „A festőnek nem csak azt kell festenie, amit maga előtt lát, hanem azt is, amit magában lát.” Ez a romantika művészetfelfogásának tételmondata is lehetne, hiszen ebben a korszakban a művész érzésvilága határozta meg a műveket, a természetbe is emberi hangulatokat vetítettek bele az alkotók. Friedrich képeinek állandó jellemzője, hogy a kép előterében a nézőnek háttal álló figurákat helyez a tájba – jó módszer ez arra, hogy a néző azonosulhasson a képi alakokkal és maga is „belekerüljön a képbe”, hiszen ugyanazt szemléli ő is, mint a kép szereplői. Jelen esetben a Holdat, amely változékonyságával, földön túli fényeivel a megfoghatatlan, messzi dolgok utáni romantikus vágyakozás célpontját is megjeleníti. A Holdat és a két férfialakot egy átlós vonalban kidőlő, korhadt tölgy és egy fenyő keretezi. Előbbi az elmúlást, utóbbi örökzöldként az örök életet, újjászületést jelképezi, mint ahogy a fogyó, majd mindig újra növekedni kezdő Hold is.

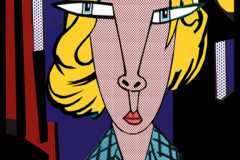

Friedrich, Caspar David (1774–1840): Two Men Contemplating the Moon, 1819–20 (oil on canvas, 33 x 44.5 cm, Galerie Neue Meister, Dresden). One of the most iconic works of German Romantic landscape painting, this image has become emblematic of the era, containing all the key features of Romanticism: a nocturnal atmosphere, the mysterious glow of the moon, dramatic elements of nature, and the small, reflective human figures nestled within it. In Ruben Brandt, Collector, a forest clearing reminiscent of Friedrich’s painting becomes the setting for a psychodramatic therapy session based on Little Red Riding Hood.

Friedrich’s landscapes are uniquely suited for inner work, as the painter himself often worked from within. Though he produced many detailed sketches of his beloved northern landscapes, he believed: “The painter should not only paint what he sees before him, but also what he sees within him.” This could well serve as the guiding principle of Romantic art, where the artist’s emotional world shaped the work, and nature became a mirror for human feeling.

A hallmark of Friedrich’s paintings is the recurring motif of figures seen from behind, placed in the foreground and gazing into the landscape. This device invites the viewer to identify with the figures and imaginatively enter the scene—seeing exactly what they see. Here, the object of contemplation is the moon, a symbol of the unattainable and the mysterious, drawing forth a deep, romantic yearning.

The moon and the two men are framed diagonally by a fallen, decaying oak and a tall fir tree. The oak signifies mortality and transience, while the evergreen pine represents eternal life and rebirth—just like the waning moon, which inevitably begins to grow again. The entire scene is steeped in quiet symbolism, evoking a moment of timeless reflection suspended between the earthly and the otherworldly.