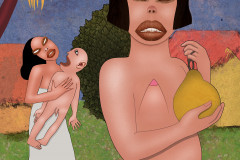

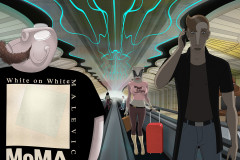

Manet, Edouard (1832-1883): Reggeli a szabadban, 1863 (olaj, vászon, 208 x 265 cm), Párizs, Musée d'Orsay. Az Olympiához hasonlóan ez a kép is hatalmas botrányt keltett első kiállításakor a közönség és a kritikusok körében is. Megint a meztelenséggel és a festésmóddal volt probléma. Nem is kapott helyett a szokásos, éves „termést” bemutató párizsi Szalonon, ahol 1863-ban olyan sokan jártak így, hogy meg is alapították a „Visszautasítottak Szalonját”. Valami – egyfajta festő forradalom - tehát szemmel láthatólag készülődött Párizsban. Pár év kellett már csak ahhoz, hogy az impresszionisták vezetésével valóban kitörjön, majd nyerjen. Manapság már a világ leghíresebb alkotásai között van ez a mű is - ahogy a Ruben Brandtban is látjuk -, a Musée d'Orsay falán, sőt, ami igazán nagy „karrier” egy festmény számára: egy turista pólóján is megjelenik a chicagói repülőtéren.

Manet előszeretettel fordult inspirációért a klasszikus reneszánsz festőkhöz. Ennek a képnek az egyik forrása is – akárcsak az Olympiánál – a XVI. század eleji velencei festő, Giorgione, akinek Koncert c. festményén, ugyanúgy a szabadban, két felöltözött férfi társaságában van két mezítelen nő. Csakhogy ott a nők nem néznek ránk, ők szinte az idillikus tájhoz tartoznak – múzsák, akik a zenélő férfiak mellett az ihletet jelképezik. Elvont, mitológiára utaló téma tehát – s a meztelenség a 19. századi polgári szalonok világában is még mindig csak így volt elfogadható. De Manet-t nem a Vénuszok és a pásztori idill érdekelte, hanem az „itt és most”, a jelen kor valósága az, amelyet be akart emelni a művészetbe. A Reggeli a szabadban modelljei pontosan felismerhetőek: Manet bátyja, annak sógora és az Olympián is láthatóVictorine Meurent, Manet kedvenc modellje foglalnak helyet fesztelenül a kép előterében. A nő élénk, beszédes tekintettel néz ki ránk a képből, nyoma sincs rajta szégyenérzetnek, mintha a világ legtermészetesebb dolga lenne talpig-kalapig felöltözött férfiakkal meztelenül csevegni. Az alakok mellett a kosárból lazán a néző elé boruló ennivalók csendélete is ezt a fesztelenséget erősíti. A kép alakjai, köszönik, renben vannak a szituációval, s most már a nézőn a sor, hogy állást foglaljon. Neked hogy tetszik a kép?

Édouard Manet (1832–1883): Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1863

Oil on canvas, 208 x 265 cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Like Olympia, this painting also caused an enormous scandal when it was first exhibited—rejected by the official Salon, it found a home instead at the newly established "Salon des Refusés" (Salon of the Rejected) in 1863, which showcased works that had been denied entry into the traditional annual Paris Salon. Something revolutionary was clearly brewing in the art world, and only a few years later, the Impressionists would break through and transform art history. Today, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe ranks among the world’s most iconic paintings—as it does in Ruben Brandt, Collector, where it appears both on the Musée d’Orsay’s wall and, in a tongue-in-cheek nod to its fame, printed on a tourist’s T-shirt at Chicago airport.

Manet often turned to the Renaissance masters for inspiration. Just like Olympia, this painting draws from the work of the early 16th-century Venetian painter Giorgione—specifically his Pastoral Concert, where two clothed men sit in the countryside with two nude women. But in Giorgione’s version, the women are ethereal, symbolic, seemingly unaware of the viewer—muses or mythological beings. Manet, however, brings the theme into the 19th century, stripping it of allegory and placing it firmly in the real world. His models are identifiable: his brother, his brother-in-law, and Victorine Meurent, the same woman featured in Olympia.

Victorine gazes directly at us, unabashed and self-possessed. She seems perfectly at ease chatting naked with fully dressed men—an image that shocked the contemporary audience not only for its content, but because of how it was painted. Manet uses broad, flat areas of color and sharp contrasts of light and dark, breaking with traditional modeling and perspective. Even the picnic still life in the foreground—food tumbling casually from a basket—feels spontaneous and modern.

Everyone in the painting seems comfortable with the situation. The only one left to respond… is us.

So—how does the picture strike you?