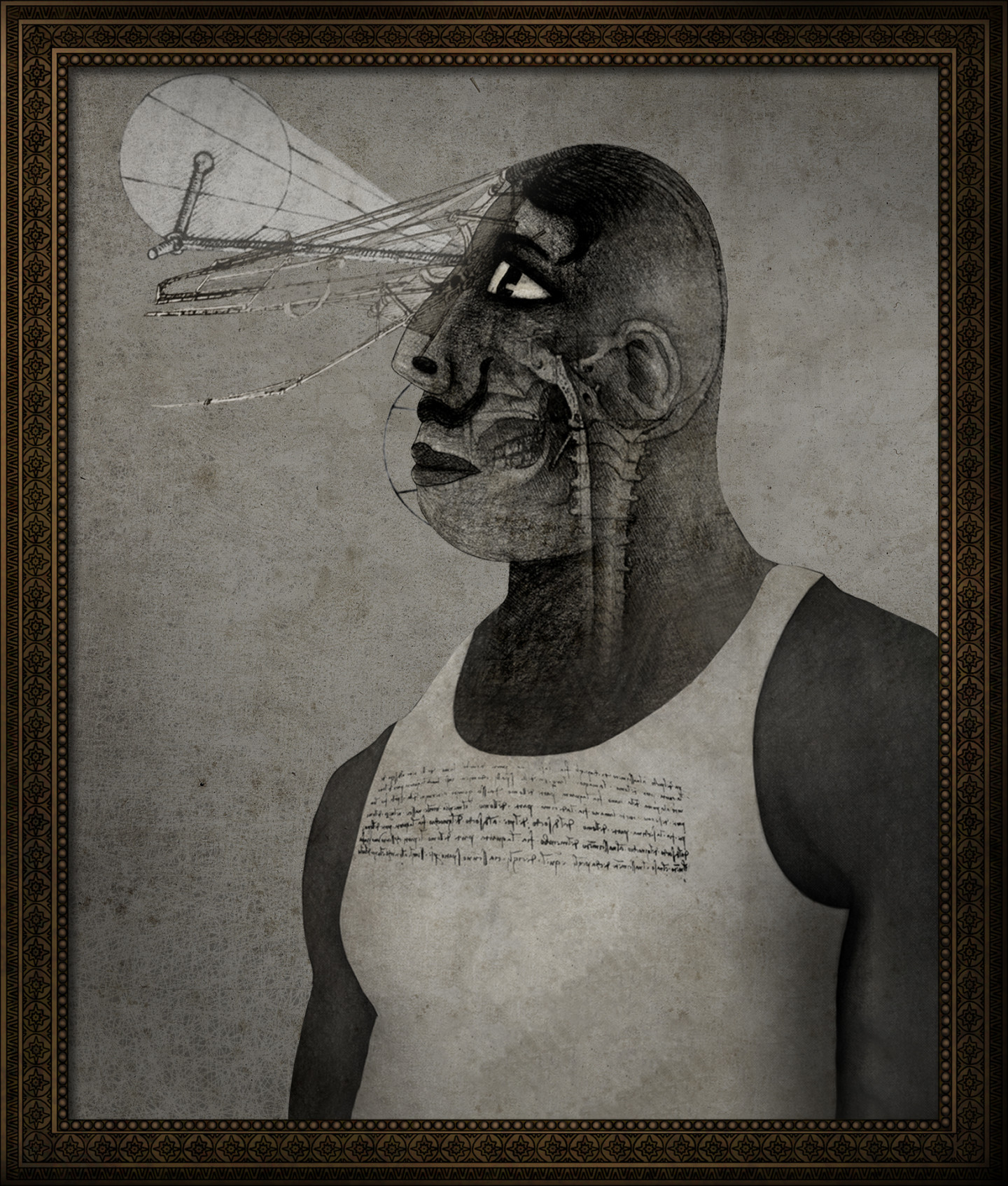

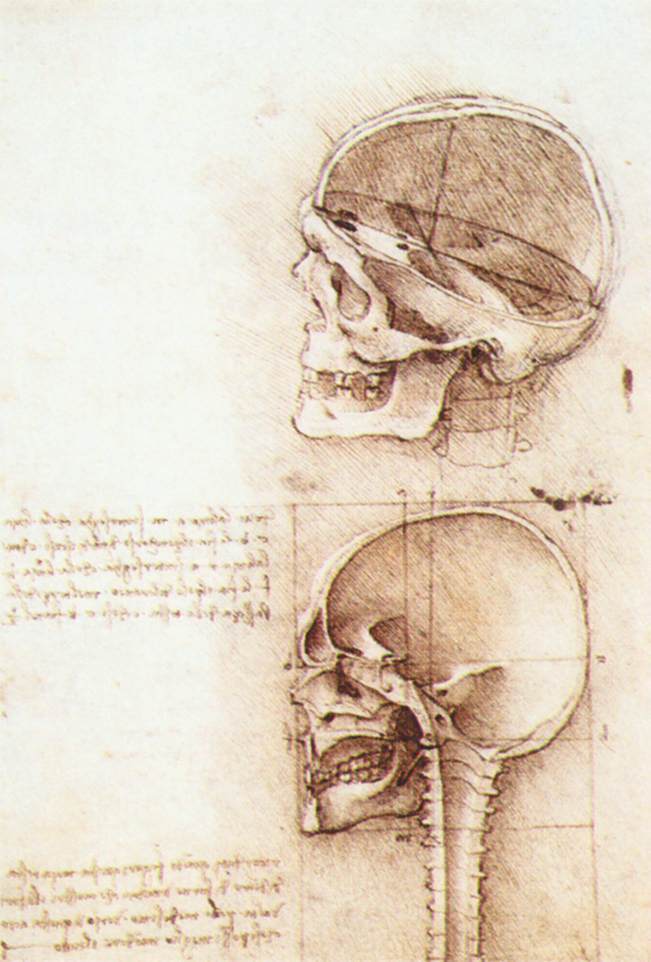

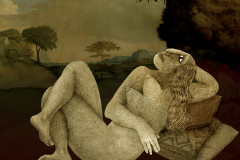

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519): Anatómiai tanulmányok – emberi koponya, 1489 (toll, tinta, kréta papír, 188 x 134 mm; Royal Library, Windsor). Az itáliai reneszánsz egyik legnagyobb zsenije törhetetlen kíváncsisággal akarta megismerni az őt körülvevő világ minden szegletét. Az embert is. Megszállottan kutatta az anatómiát, emberábrázolásai mögött ott van ez a hihetetlen mennyiségű tudás, amit rajzai és jegyzetei is őriznek. A Ruben Brandtban a Musée d'Orsayben láthatunk egy olyan fiktív verziót, ahol anatómiai tanulmány és arckép egy műben találkozik.

Manapság mindenki látott már legalább egy röntgenfelvételt valamelyik testrészéről vagy már óvodás korában ismerkedni kezdett a „Hogyan működik a testünk?” típusú könyvek segítségével az anatómia alapjaival. A középkorban és a korareneszánszban azonban a legnagyobb művészek és tudósok számára sem álltak rendelkezésre pontos ábrázolások, tapasztalati úton kellett feltérképezniük az emberi test felépítését, épp úgy, ahogy a nagy földrajzi felfedezőknek a földrészek elhelyezkedését. Leonardo olyannyira érdeklődött a téma iránt, hogy az 1500-as évek elején Marcantonio della Torréval, a paviai egyetem orvosprofesszorával ő maga is nekiállt holttesteket boncolni. Ez a rendkívüli lehetőség már szinte tudományos szintre emelte Leonardo rajzait, nem csak az emberi testet alkotó elemek felfedezéséről szólnak ezek a munkák, hanem a különböző alrendszerek – csontok, izmok, inak – együttműködését is vizsgálja. Lenyűgöző precizitás, tudós alaposság, miközben festményeiből nem vész ki a költészet, a megmagyarázhatatlan vonzerő.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519): Anatomical Studies – Human Skull, 1489 (pen, ink, chalk on paper, 188 x 134 mm, Royal Library, Windsor). One of the greatest geniuses of the Italian Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci pursued a relentless curiosity about every aspect of the world around him—including the human body. His obsession with anatomy lies behind the extraordinary knowledge embedded in his human figures, preserved in both his drawings and notes. In Ruben Brandt, Collector, a fictional version of this study appears at the Musée d'Orsay, combining anatomical sketch and portrait into a single image.

Today, most people have seen at least one X-ray of their own body, and children are introduced to anatomy through books like How Our Body Works from an early age. In the Middle Ages and early Renaissance, however, even the most accomplished artists and scholars had no access to accurate anatomical references—they had to chart the human body through direct observation, just as explorers mapped the continents. Leonardo’s passion for the subject led him, in the early 1500s, to work alongside Marcantonio della Torre, a professor of medicine at the University of Pavia, performing dissections on human corpses.

This extraordinary access elevated Leonardo’s anatomical studies to near-scientific status. His drawings are not just about discovering the individual elements of the human body, but also about understanding the coordinated function of its subsystems—bones, muscles, tendons. They reflect stunning precision and scholarly rigor, yet Leonardo’s paintings never lose their poetry, nor their enigmatic, irresistible allure.