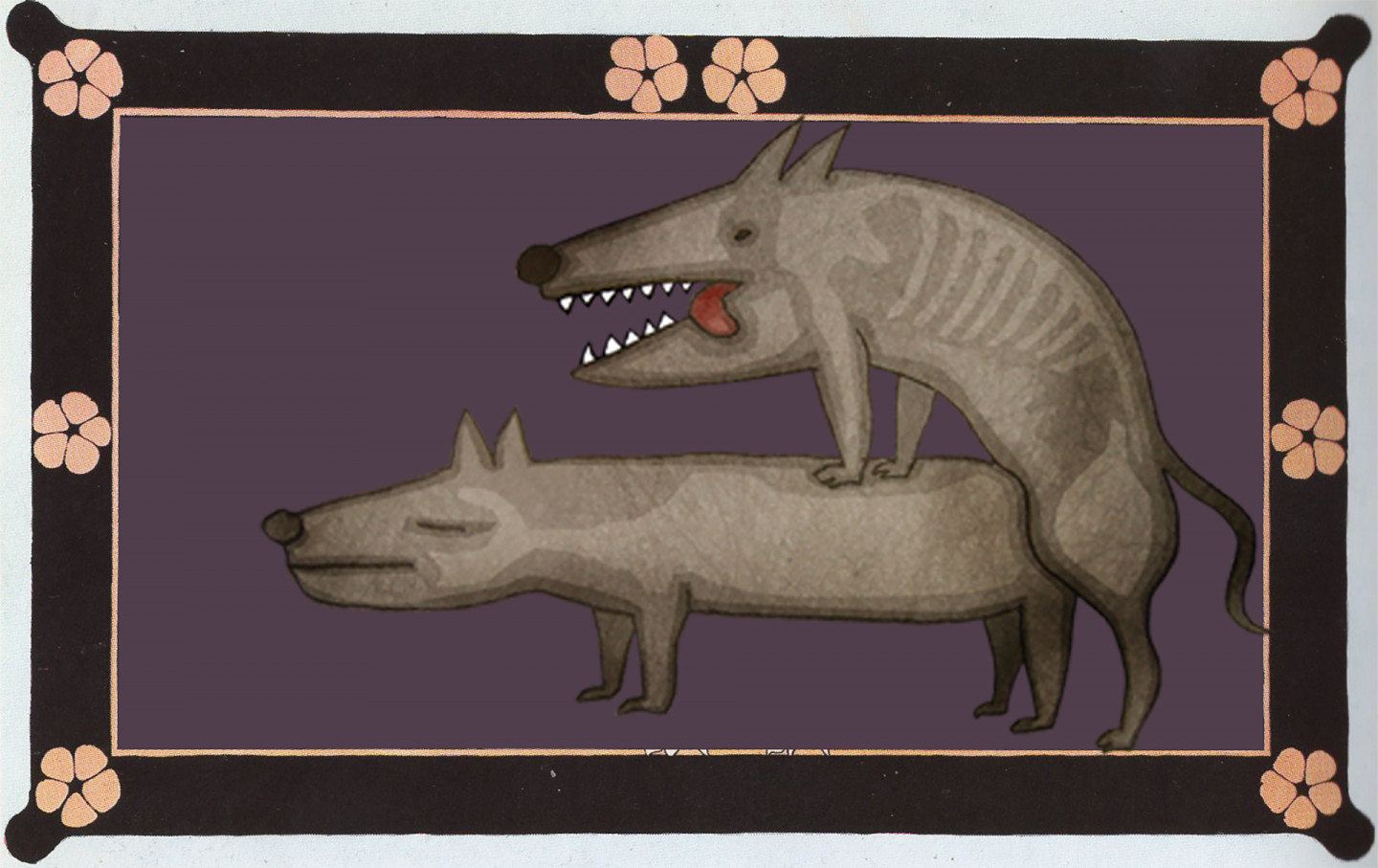

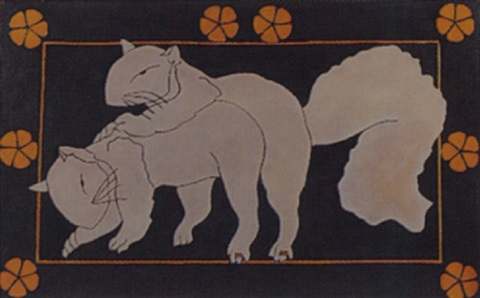

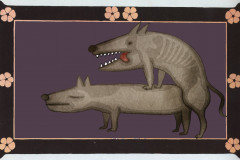

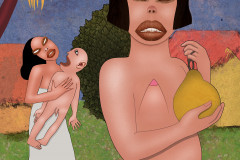

Wesley, John (1928-): Mókusok 1965 (akril, vászon, 76 x 120cm, magántulajdon). Az amerikai festőművészt minimalista, képregényszerű stílusa miatt leginkább a pop-arthoz szokták sorolni, bár őt kevésbé a tömegkultúra manipulált képei, mintsem inkább az egyén pszichéjének vágyai, félelmei, fantáziái érdeklik – mint pl. a paráználkodó mókusok. A Ruben Brandtban a tokiói pop-art-kiállításon szereplő átalakított verzión a „cukiság-sorban” előkelő helyen álló mókusokat a félelmetesebb farkasok helyettesítik, felvillantva a Ruben Brandt terápiás munkájában korábban szereplő „Piroska és farkas”-motívumot.

Wesley önmagát mindig inkább szürrealistának tartotta, aki azért fordul a leegyszerűsített szín- és formanyelv felé, hogy a lecsupaszított lényegre irányítsa a figyelmet, a tudatalattiban tárolt sűrítményeket hozza felszínre. Képeit átszövi az erotika, s párhuzamos szálként állatok képei is gyakran megjelennek alkotásaiban – akár díszítőmotívumként, akár „főszereplőként”. A párzó mókusokat ábrázoló festménye kifigurázza a közmegegyezés szerint aranyos, mogyorót majszoló, de valójában meglehetősen agresszív állatról alkotott képünket. Szexualitásukban emberi jegyekkel ruházza fel őket, hiszen mindkét állat lábán gyűrű látható, az emberi kapcsolatok, összetartás szimbóluma. A közösülés állati formájával ironikus ellentétben áll a kép szélének virágos díszítőmotívuma, amelynek gyakori használata miatt Wesley képeinél a rokokó és pop-art találkozását is szokták emlegetni. Mintha egy kislányszoba falára szánt képkeretbe került volna véletlenül korhatáros kép (vagy csak valóban a tudatalatti fantáziák szabadultak el).

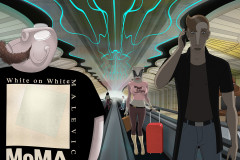

Wesley, John (1928–): Squirrels, 1965

(acrylic on canvas, 76 x 120 cm, private collection)

John Wesley, the American painter often associated with pop art, carved out a singular niche with his flat, pastel-hued, cartoon-like images. But while his style visually echoes the aesthetics of comics and consumer graphics, Wesley himself identified more with surrealism. He was less concerned with mass media and more fascinated by the subconscious: desire, fear, absurdity, and repression—all of which surface in works like Squirrels. In Ruben Brandt, Collector, an altered version of this piece appears at the Tokyo pop-art exhibition, where the squirrels are replaced by menacing wolves, invoking the film’s recurring Little Red Riding Hood motif and its psychoanalytic overtones.

Wesley’s Squirrels is deceptively innocent at first glance. With its pastel palette and symmetrical layout, it might resemble wallpaper or a decorative panel from a child’s room. But a closer look reveals the unexpected: two squirrels mid-coitus, both wearing wedding rings. It’s a collision of cuteness and carnality, of animal instinct and human symbolism. The rings humanize the squirrels—mocking conventional associations of love, fidelity, and domesticity. Meanwhile, the floral border pattern adds a veneer of decorative charm that clashes ironically with the explicit central scene.

Wesley often used animals in his work—sometimes as metaphors, sometimes as protagonists. He played with their perceived innocence or aggression, turning symbols of domestic comfort (like squirrels or rabbits) into unsettling stand-ins for human behavior. The stylized, almost antiseptic execution—a hallmark of Wesley’s minimalist graphic approach—amplifies this tension. As with many of his works, the humor is dry, the eroticism is veiled but unmistakable, and the tone is both playful and unnerving.

In the context of Ruben Brandt, Collector, the substitution of wolves for squirrels deepens this duality. It taps into the Jungian shadow—the lurking, primal fears beneath the veneer of innocence. Wesley’s Squirrels thus fits seamlessly into the film’s exploration of the unconscious, where cartoon logic, symbolic transformation, and trauma intertwine in both therapeutic and dangerous ways.