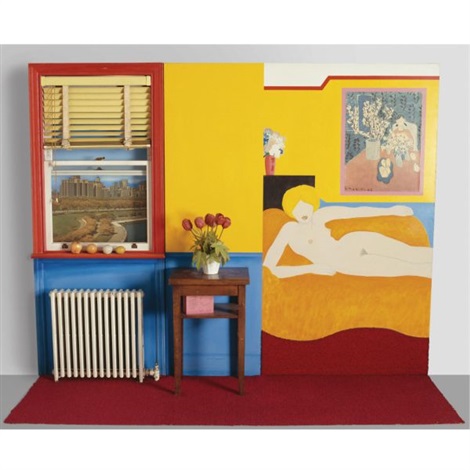

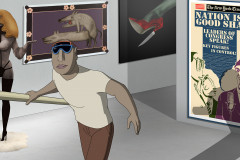

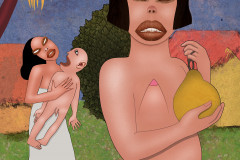

Wesselmann, Tom (1931-2004): Nagy amerikai akt No. 48, 1963 (vegyes technika, 213,3 x 271,1 x 102,8cm, magántulajdon). Az amerikai pop-art legjelentősebb alkotói közé tartozó festő a '60-as években készítette el az abban az időben nyílt, kihívó szexualitása miatt provokatívnak számító „Nagy amerikai akt sorozatát”. Nemcsak témájában, hanem technikájában is újító jellegű sorozatról van szó, hiszen Wesselmann a festészeti részek mellé valóságos tárgyakat is beemel a kompozíciókba. A Ruben Brandtban a képen látható fekvő akt testtartására ismerhetünk rá abban, ahogy Mimi heverészik a tengerparton. És még egy kapcsolat a filmmel: Wesselmann műve is tartalmaz finom utalásokat klasszikus festményekre. Vajon melyekre?

Maga a sorozat címe, a „Nagy amerikai akt” is azt sugallja, hogy itt valamiféle párbeszéd indul az „európai akt” nagy hagyományával. Wesselmannra saját bevallása szerint az európai festészetből Matisse volt legnagyobb hatással, akinek rajongva csodálta műveit, - ahogy fogalmazott - a belőlük áradó szépség miatt. Az élénk, energiával teli színvilág, a dekoratív, síkszerű festett felületek valóban rokonítják Wesselmann műveit Matisséival, aki számos enteriőrben elhelyezett aktot is alkotott. A „Nagy amerikai akt No. 48”-ba egy konkrét idézet is be van építve a mestertől: a nő fölött a falon egy Matisse-csendélet lóg. De az aktfestészetre természetesen régebbi példákat is találhatunk, melyekkel a Ruben Brandt-filmben is találkozunk: az érett reneszánsz képviselőjének, Tiziánónak Urbinói Vénusza nyilvánvaló parafrázisokat is inspirált (l. Manet Olympiája), de hatása még itt, Wesselmann-nál is felismerhető: az ágyon felkönyöklő, a nézőre kitekintő testhelyzet, a belső tér két részre tagolt szerkezete eszünkbe juttathatják a klasszikus művet. Csak épp itt megfordul a terek elrendezése: a nő fekszik a szoba hátsó részében, az ablakkal megnyitott rész pedig előrébb helyezkedik el. A valódi tárgyak (ablakkeret, radiátor, kisszekrény) beépítésével valóban háromdimenzióssá válik ez az előtér, a határ a néző világával összemosódik. Akár be is léphetnénk ebbe a nappaliba... Mint a pop-art alkotások esetében oly sokszor, megint szembetaláljuk magunkat azzal a kérdéssel, hogy meddig tart a valóság és hol kezdődik a művészet. (A problémafelvetés a Ruben Brandt-filmtől sem idegen...)

Wesselmann, Tom (1931–2004): Great American Nude No. 48, 1963 (mixed media, 213.3 x 271.1 x 102.8 cm, private collection). One of the leading figures of American pop art, Wesselmann created his Great American Nude series in the 1960s—works that were provocative at the time for their bold, unapologetic sexuality. But the series was also innovative in technique: alongside painted elements, Wesselmann incorporated real, three-dimensional objects. In Ruben Brandt, Collector, the reclining pose of the nude in this piece is mirrored in how Mimi lounges on the beach. And there's another connection: Wesselmann’s work contains subtle allusions to classical paintings, just as the film constantly references art history.

The very title Great American Nude suggests a deliberate dialogue with the European tradition of the nude. Wesselmann himself cited Henri Matisse as his greatest influence—drawn to the beauty, vibrancy, and emotional immediacy of his work. Wesselmann’s flat, decorative color fields and energetic palette reflect that influence, as does his use of nudes placed within domestic interiors—a direct nod to Matisse’s own compositions. In No. 48, Wesselmann even quotes Matisse explicitly: a still life by the master hangs above the reclining woman, bridging old and new.

But the line of reference stretches further back. The reclining nude is a recurring motif in Western art, and Great American Nude No. 48 echoes Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538)—a work already reinterpreted by Manet in his Olympia (1863), both of which feature in Ruben Brandt, Collector. The pose—propped on an elbow, gazing at the viewer—is unmistakable. Wesselmann keeps this composition, but rearranges the space: unlike Titian’s Venus, his nude lies toward the back of the room, while the foreground, with its open window and furniture, is brought closer to the viewer. The addition of real objects like a radiator or window frame makes this scene feel more immersive, almost enterable—blurring the line between artwork and everyday life.

That’s a key hallmark of pop art: constantly questioning where art ends and reality begins. This tension is also at the heart of Ruben Brandt, Collector, where artworks come alive, cross over into dreams, and shape personal identity. Just as Wesselmann’s Great American Nude series asks us to rethink the role of beauty, tradition, and the body, the film invites viewers into a world where reality and representation are inseparably intertwined.