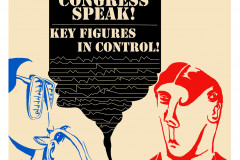

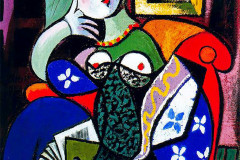

Friedrich, Caspar David (1774-1840): Vándor a ködtenger felett, 1818 (olaj, vászon, 95 x 75 cm) Kunsthalle, Hamburg. A német romantika talán leghíresebb festménye fenséges tájban, mintegy „a világ tetején” álló magányos férfisziluettet ábrázol, amelyhez hasonló alak a film plakátján is feltűnik. Mimi álmában látja meg a dombtetőn háttal álló Ruben Brandtot (?), s „Szabad vagyok!” kiáltással fut felé, aki, amikor megfordul, a lányt üldöző Kowalskivá válik... Mimi riadtan ébred. Szabadság és rettegés – mindkét érzés a romantika alapmotívuma, összetartoznak, mint ahogy a filmben Ruben Brandt és Kowalski.

Érzésekkel telítődik meg a képen látható táj is, amelyet a hegytetőn álló vándorral együtt mi is szemlélünk. Szabadság, elért siker, elégedettség, végtelenség, magány, „vége”-érzés, szakadékbaugrás, izgalom, tériszony... ezek az érzések mind eszünkbe juthatnak a kép kapcsán. Szerinted, ha Te állnál ott, mit éreznél? A Friedrich által gyakran használt megoldás, a nézőnek hátat fordító emberi alak itt különösen hangsúlyos, hiszen a kép közepén áll, nagy mérete miatt, mintha mi is ott állnánk mögötte, hamarosan fölérve a csúcsra. Ellenfényben látszó alakja inkább csak egy sötét sziluett, amelytől még titokzatosabb a kép – ki lehet a férfiú, honnan érkezett ide, mit lát, ha lenéz? stb. A romantikus táj sohasem eseménytelen, ez az irányzat a természetben, mint az emberben is, az egyedit, gyakran szélsőségest keresi. A kopár, felhők fölé magasodó sziklás hegycsúcs ilyen. Lélegzetelállító, megállásra késztető. A „vándor” itt szimbolikusan az életet élő ember is lehet, aki célját elérve, sorsdöntő kérdésekkel találkozik, s itt, az emberi világ fölé emelkedve, az istenivel is kapcsolatba kerülhet.

Friedrich, Caspar David (1774–1840): Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818 (oil on canvas, 95 x 75 cm, Kunsthalle, Hamburg). Perhaps the most famous painting of German Romanticism, this iconic work depicts a solitary male figure standing atop a rocky peak, gazing out over a swirling, cloud-covered landscape. A similar silhouette appears on the Ruben Brandt, Collector film poster. In Mimi’s dream, she sees Ruben Brandt (or someone she believes to be him) standing with his back turned atop a hill. She runs toward him, shouting “I’m free!”—but as he turns around, he becomes Kowalski, her pursuer. Mimi wakes up in terror. Freedom and fear—two core themes of Romanticism—are bound together, just as Ruben and Kowalski are in the film.

The landscape in Friedrich’s painting is infused with emotion, which we as viewers share with the solitary figure. Freedom, triumph, awe, loneliness, finality, vertigo, transcendence—any or all of these may come to mind when contemplating the scene. What would you feel, if you stood there?

The motif of a figure seen from behind—a frequent device in Friedrich’s art—is especially powerful here. Placed at the very center of the composition and rendered large in scale, the wanderer acts as a stand-in for us. It feels as though we’ve just climbed to this very spot and are catching our breath before taking in the view. His backlit silhouette adds to the mystery: who is he, where has he come from, what does he see?

Romantic landscapes are never static—they seek the extraordinary, the sublime, often the extreme. The barren, jagged peak rising above the clouds embodies this search. It is breathtaking, arresting. The “wanderer” becomes a metaphor for human existence, reaching a symbolic summit where decisive questions arise—and where one might, for a moment, touch the divine.