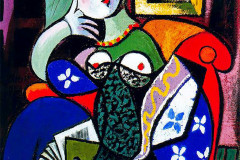

Bronzino, Agnolo (1503-72): Toledói Eleonóra képmása, 1544-45 (olaj, fatábla, 115 x 96 cm) Uffizi, Firenze. A firenzei nagyherceg, I. Cosimo de Medici feleségét és fiát, Giovannit ábrázoló portré az itáliai manierizmus jellegzetes alkotása – a korra jellemző hideg precizitással, életidegenséggel megfestett nőalak a filmben Firenze főterén tűnik fel (ahol a festményt őrző Uffizi is található), amint épp telefonnal készít róla valaki egy fényképet.

A reneszánsz idején kiemelkedő műfajjá váló portré az egyéniség megragadására törekedett, az embert környezetével, a természettel összhangban, arra nyitottan ábrázolta. A reneszánszot követő manierizmus azonban pont ezzel a természetességgel szakít, megjelennek a modern korra is oly jellemző kétségek: mi az, ami egyáltalán megmutatható? Biztosan megismerhető-e ez a világ, amely nem is tűnik már olyan harmonikusnak? Mi benne a valódi és mi az álca? Ebből a kettős portréból, mely a rideg spanyol udvarból származó Eleonórát kb. 26 éves korában ábrázolja, 11 gyermeke közül a másodikkal, mindenfajta érzelem, anyai gyengédség hiányzik. Uralkodói elegancia és merevség jellemzi a beállítást, a technikai tökéletesség, kifinomult részletek mögött eltűnik az ember természetes elevensége. Mintha Eleonóra aprólékos rajzolatú, súlyos, hímzett bársonyruhájába mint egy kaltikába lenne bezárva. Az alakok mögötti hideg, fémes-kék háttérben nagy sokára fedezzük csak fel a jobb szélen a táji részletet, folyóval és lankás dombokkal, de mennyire más ez a táj, mint a fénnyel átítatott, tekintetünket a távolba engedő reneszánsz tájak! Itt nincs már felszabadult szabadság... Anya és kisfia képmásai annyira élethűek, mint a viaszpanoptikum bábui – minden aprólékosan le van másolva, csak az élet hiányzik belőlük.

Bronzino, Agnolo (1503–1572): Portrait of Eleonora of Toledo, 1544–45 (oil on panel, 115 x 96 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence). This double portrait of Eleonora of Toledo, wife of Cosimo I de’ Medici, and their son Giovanni is a hallmark of Italian Mannerism—its precise, almost lifeless execution standing in stark contrast to the warmth of earlier Renaissance portraiture. In Ruben Brandt, Collector, the painting makes an appearance in Florence’s main square—right outside the Uffizi—just as someone snaps a photo of it with their phone.

Portraiture reached new heights during the Renaissance, aiming to capture not just likeness but inner character, placing the individual in harmony with nature and the world around them. Mannerism, the style that followed, broke with this naturalism, introducing doubts that resonate with modern sensibilities: What can truly be shown? Can the world still be understood? What is real and what is mere façade?

This portrait shows Eleonora—about 26 years old at the time, from the austere Spanish court—alongside her second son. But there’s no maternal warmth, no emotional bond between mother and child. Instead, there is the cold elegance of nobility: formal posture, technical brilliance, and elaborate detail, but no trace of spontaneous life. Eleonora appears entombed in her richly embroidered velvet gown, its heavy, ornate fabric acting almost like armor. Behind her, the metallic blue background barely reveals a distant landscape—river and hills faintly visible on the right edge. But this is no luminous Renaissance vista inviting the eye into open space. This world is sealed, rigid, constrained.

The figures are stunningly lifelike, yet almost waxen—like sculptures from a museum of courtly decorum. Every detail is painstakingly rendered, and yet what’s missing is the vital spark of lived human presence.