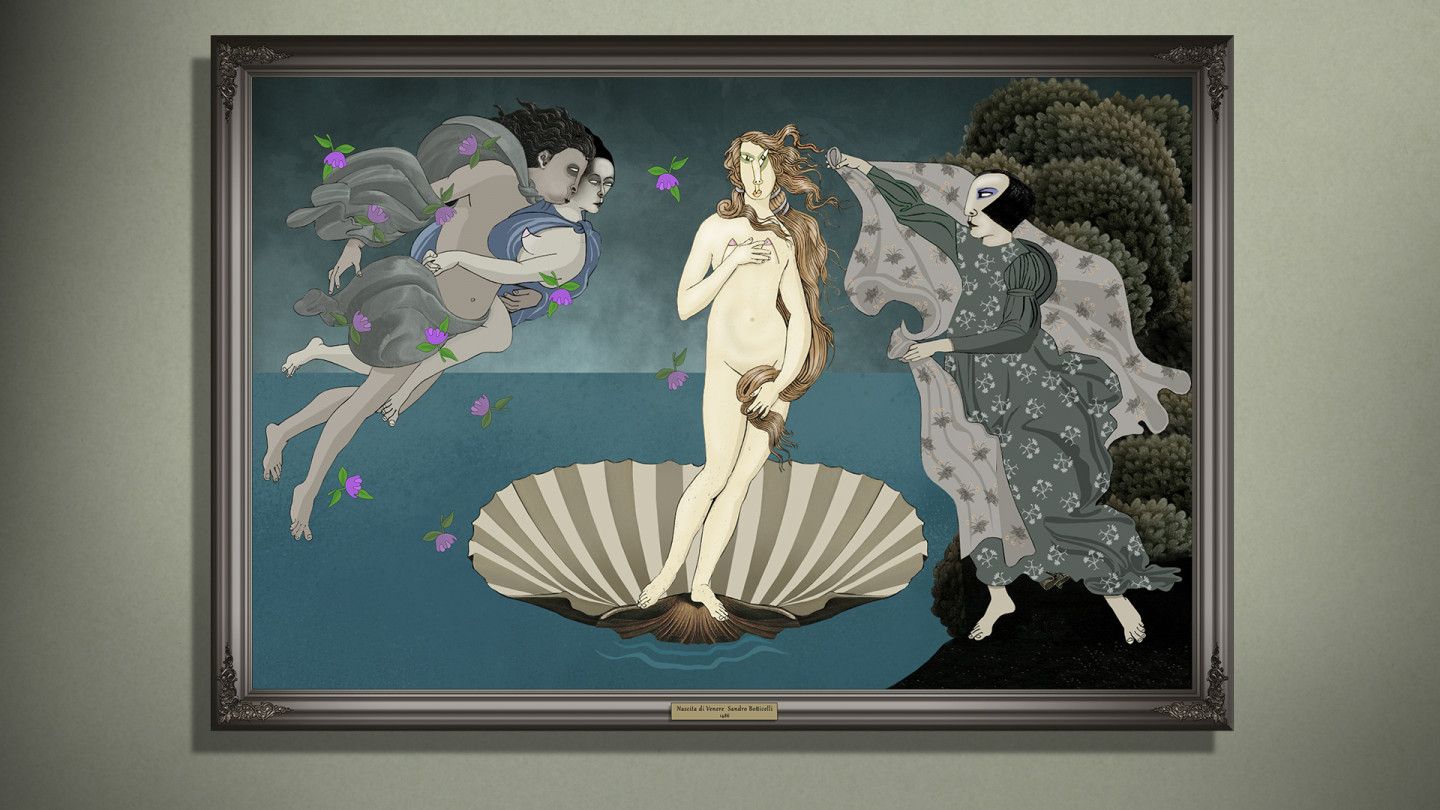

Botticelli, Sandro (1445 – 1510): Vénusz születése, 1485 k. (tempera, vászon, 172,5 x 278,5 cm; Firenze, Uffizi), az itáliai reneszánsz egyik legismertebb alkotása. A szépség és szerelem római istennőjét ábrázoló kép a klasszikus női szépség „ikonjává” vált, mely Ruben Brandtot is megigézte, benne is van a 13 elrabolt alkotásban.

Botticelli az 1480-as évek Firenzéjének egyik legnépszerűbb festője volt, akit a várost vezető Mediciek is sokat foglalkoztattak. A Vénusz születése címen híressé vált mű is az ő megbízásukból készült, valószínűleg egy nyaralójukat díszítette – ezért is van a korban még inkább szokásos fatábla helyett a könnyebben szállítható vászonra festve – és így legalább a filmbeli műkincsrablók is könnyebben kivághatták a keretéből. Vénusz a mitológia szerint a tenger habjaiból született. A kép azonban már a történet további részét ábrázolja, ahogy Vénuszt egy kagylón állva (amely egyébként a nőiség szimbóluma), Zefír szélistenség és Aura, a szellő partra fújják. Vénusz hajzuhatagának lobogó fürtjei tanúskodnak az erős szélről, a filmben még a képből is kilebegnek, s pont ezek azok, amik „berántják” Rubent a képbe. A festményen az istennő márványszerű alakja nyugodt, lágy S-alakot felvevő testtartása (kontraposzt) azokat az ókori római Vénusz-szobrokat idézi, melyek másolásával a reneszánszban a művészek az aktábrázolást elsajátították. A partra érkező istennőt az évszakokat megtestesítő Hórák egyike fogadja, kezében tavaszi virágokkal teli lepel vár Vénusz felöltöztetésére, hiszen milyen más évszakban is születhetne a Szerelem, ha nem tavasszal? A szélben repkedő üde rózsák arra a legendára utalnak, mely szerint a rózsa Vénusz születésekor virágzott először, ezért is jelképezheti mind a mai napig a szerelmet.

Botticelli, Sandro (1445–1510): The Birth of Venus, c. 1485

(tempera on canvas, 172.5 × 278.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence)

One of the most iconic masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance, The Birth of Venus depicts the Roman goddess of love and beauty emerging from the sea. In Ruben Brandt, Collector, the painting is one of the 13 stolen artworks, and its ethereal allure proves irresistible—even to the troubled psyche of Ruben himself. The goddess’s flowing hair, caught in the sea breeze, doesn’t just hint at the wind gods Zéphyr and Aura propelling her to shore; in the film, her golden locks billow beyond the canvas, reaching out—literally dragging Ruben into the painting.

Botticelli was among Florence’s most sought-after painters in the 1480s, working frequently under the patronage of the Medici family. This particular work was likely commissioned for a Medici countryside villa, which may explain why it was painted on canvas—a lighter, more portable material than the wood panels typical of the time. This choice of support makes the painting’s filmic abduction slightly more plausible: it's easier to cut loose, carry, and escape with.

The scene illustrates the moment after Venus’s mythical birth: standing on a giant scallop shell (a classical symbol of femininity), she is blown ashore by the wind gods, while one of the Horae, personifications of the seasons, awaits to clothe her with a floral-embroidered mantle. Botticelli's Venus embodies the Renaissance ideal of beauty—graceful, serene, and perfectly poised in a contrapposto stance that echoes ancient Roman statues. Her alabaster skin, elongated neck, and impossibly fluid posture lend her an almost divine stillness, contrasting the movement around her.

The pink roses scattered by the wind are more than decorative: legend has it that roses bloomed for the first time upon Venus’s birth, marking them forever as symbols of love. The entire composition is at once mythological and allegorical, naturalistic and dreamlike, and has long stood as a visual definition of idealized love and beauty. In Ruben Brandt, this timeless image becomes not only an object of desire—but a trap. Beauty, after all, has the power to both heal and consume.