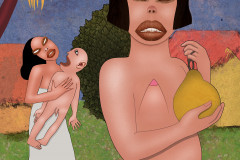

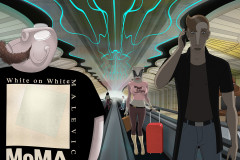

Warhol, Andy (1928-1987): Campbell konzerves dobozok, 1962 (polimer festék, vászon, egyenként 50,8 x 40,6 cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York. Az amerikai pop-art legnevesebb alkotója az átlag-amerikai polgár számára legismerősebb tárgyakat, képeket tette műalkotásai témájává. A 32-féle ízben gyártott Campbell leveskonzerv minden háztartás alapdarabja volt, a filmben John Cooper volt CIA-ügynök konyhájában is ott figyel egy epres verzió a konyhapult alatt.

Andy Warhol saját bevallása szerint 20 évig mindennap ugyanazt a leveskonzervet ette, jól tűrte hát a monotonitást. Nem okozott neki az sem gondot, hogy mechanikus pontossággal 32-szer megfesse ugyanolyan formátumban, ugyanazt a konzervdobozt, csak az ízt jelölő feliratot változtatva. Első kiállításán a sorozat egyes darabjai ugyanúgy polcokra voltak helyezve, mint a szupermarketek polcain sorakozó áruk. A műalkotás és árucikk közötti határ tudatos elmosására törekedett. Nem sokkal e kézzel, egyedien megfestett sorozat elkészülte után talált rá az ezüstszitanyomat technikájára, amellyel aztán képeit is sokszorosítani tudta, így azok még közelebb kerültek a gyárilag előállított tömegcikkekhez, illetve az azokat hirdető kereskedelmi plakátokhoz. Az egyedi exkluzív műalkotások igényével leszámolva hirdette, hogy „A művészetnek nem csak kiválasztott kevesekhez kell szólnia, hanem az amerikai emberek tömegeihez.” Neki sikerült ezt megvalósítania, hatalmas média- és közönségfigyelemmel kísért szupersztár lett (még merényletet is megkíséreltek ellene elkövetni), saját személyét is jól eladható termékké alkotta. És a receptet mindenki számára alkalmazhatónak gondolta, megjósolva korunk celebvilágának alaptételét: „A jövőben mindenki híres lesz 15 percre” - ahogy arra Ruben Brandt páciensei is hivatkoznak tokiói ál-performanszukban.

Warhol, Andy (1928–1987): Campbell’s Soup Cans, 1962 (synthetic polymer paint on canvas, each 50.8 x 40.6 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York). The most iconic figure of American pop art, Warhol turned the most familiar objects and images of the average American household into works of art. His depiction of Campbell’s soup—a staple product available in 32 varieties—became legendary. In Ruben Brandt, Collector, a strawberry-flavored can (fictional, of course) appears beneath the kitchen counter in former CIA agent John Cooper’s apartment.

According to Warhol himself, he ate the same soup every day for twenty years—he didn’t mind monotony. It’s no surprise, then, that he had no trouble painting the same soup can 32 times with mechanical precision, changing only the flavor label. At his first exhibition, the canvases were displayed like products on supermarket shelves, deliberately blurring the line between artwork and consumer good. Not long after completing this hand-painted series, Warhol began using silkscreen printing, which allowed him to mass-produce his images—bringing his works even closer to mass-produced goods and commercial posters.

Rejecting the notion of the exclusive, one-of-a-kind artwork, Warhol declared, “Art should be for everybody.” And he succeeded. He became a superstar surrounded by immense media and public attention—even surviving an assassination attempt—and transformed himself into a marketable product. His philosophy, and his persona, helped define modern celebrity culture, foreshadowing today’s fame economy with his famous prediction: “In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.” A quote echoed, fittingly, by Ruben Brandt’s patients during their mock performance in Tokyo.