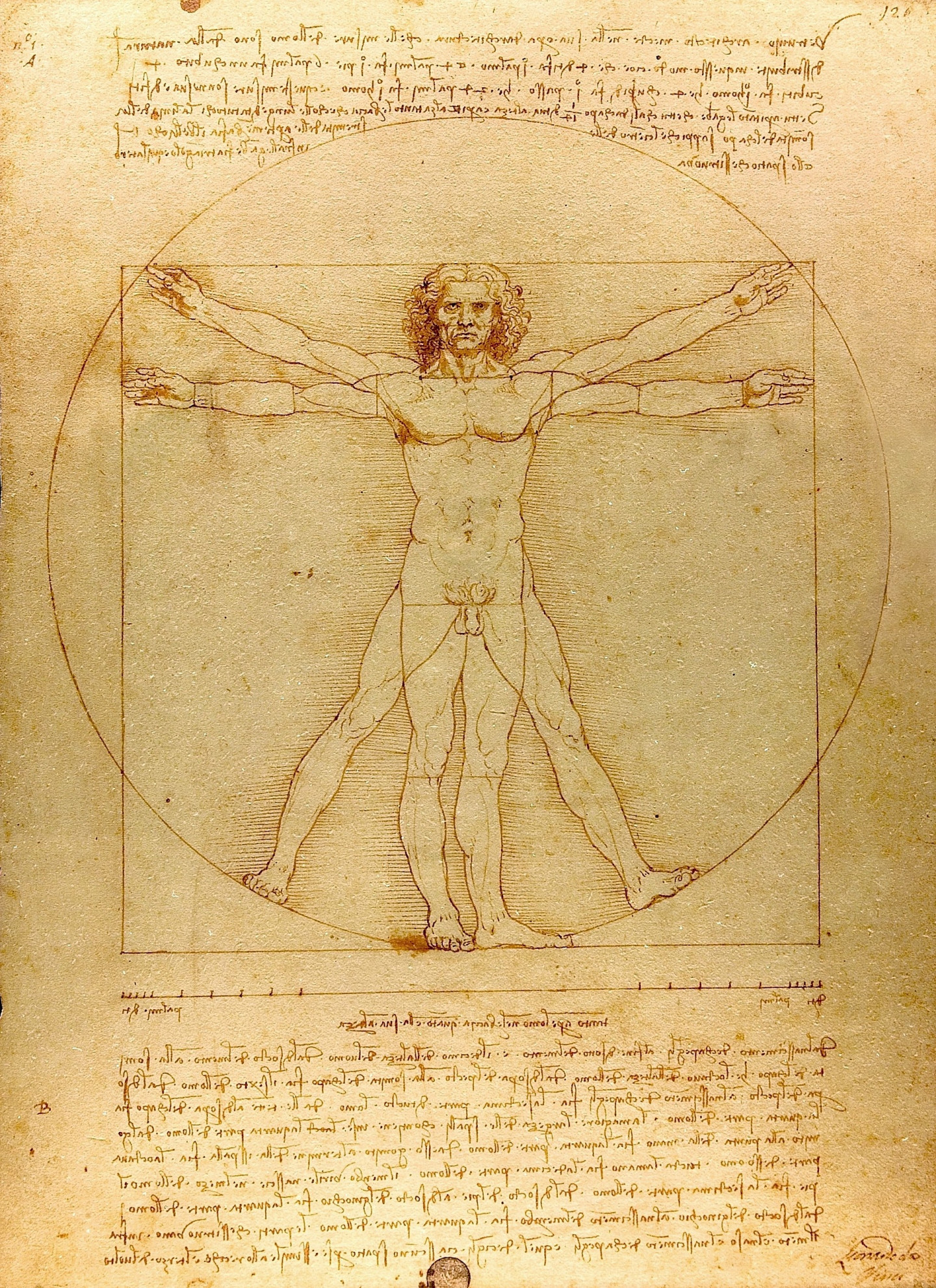

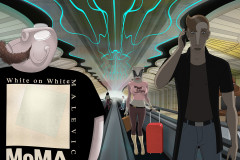

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519): „Vitruviusi ember”, 1492 (toll, tinta vízfesték, papír, 343 x 245 cm) Gallerie dell' Accademia, Velence. A nagy reneszánsz művész és polihisztor egyik leghíresebb tanulmányrajza az antik építész,Vitruvius értekezésében található, a „tökéletes emberi test” arányairól szóló leírást illusztrálja. A római, Leonardo da Vinciről elnevezett repülőtér 3-as termináljában pedig e rajzot háromdimenzióssá átültető alkotás található: Mario Ceroli „Squilibrio” ( = „egyensúlyhiány”) című 1967-es műve. E mellett haladnak el hőseink is a római reptérre jövet-menet.

Vitruvius szerint az ideális ember testfelépítése illeszkedik a tökéletes geometriai síkidomok, a kör és a négyzet formájába: ha karunkat és lábunkat széttárjuk és köldökünket tekintjük a kör középpontjának, pont beleférünk a körbe, összezárt lábakkal és vízszintes karokkal pedig pont egy négyzetbe. Próbáld ki, hogy rád vajon érvényes-e ez a megállapítás! Sokan próbálták illusztrálni ezt a híres tételt, de Leonardónak sikerült az emberi anatómiát nem torzító módon megvalósítani a kompozíciót. Nem csoda, hiszen ő több hónapon keresztül szisztematikus méréseket végzett két fiatal férfi testén, s ezeket feljegyezve, tapasztalati úton összeállított arányrendszert kapott, mely alapján Vitruvius megállapításait kissé korrigálta. Ő semmit nem hitt el „készen kapva”, mindennek utánajárt zseniálisan gyermeki kreativitásával és kíváncsiságával.

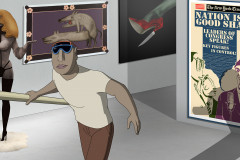

A reneszánszot általában az ideálok érdekelték, Ceroli háromdimenziós konstrukciója azt mutatja meg, milyen labilissá, törékennyé válhat ez az elméletben elképzelt egyensúly, a „tökéletes kétdimenziós ember”, ha az emberi élet realitásába, azaz a három dimenziós térbe kerül. Mint egy madzagon rángatott kis bábu. Az ideák megvalósításához, az alkotáshoz bátorság és nyitottság kell, sokszor kibillenhetünk az egyensúlyunkból, mint végül is az utazás során is – milyen remek gondolat, ezt a művet egy repülőtéren elhelyezni. Ahol ráadásul a szobrot folyamatosan találkozási pontként egyeztetik az emberek, mint ahogy a művészettörténetben Leonardo munkássága is sokak számára referenciapont.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519): Vitruvian Man, 1492 (pen, ink, watercolor on paper, 343 x 245 mm, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice). One of the Renaissance master and polymath’s most iconic study drawings, this work illustrates the proportions of the “ideal human body” as described in the treatise by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius. In the film Ruben Brandt, Collector, the characters pass by a three-dimensional interpretation of this drawing—Mario Ceroli’s Squilibrio (“Imbalance,” 1967)—while moving through Terminal 3 of Rome’s Leonardo da Vinci Airport.

According to Vitruvius, the ideal human figure fits perfectly into the two most harmonious geometric shapes: the circle and the square. If we spread our arms and legs with the navel as the center, the body fits into a circle; with feet together and arms extended horizontally, it fits into a square. Try it yourself—do you match this ancient ideal? Many have attempted to illustrate this theory, but Leonardo succeeded in doing so without distorting human anatomy. Unsurprisingly, he based the drawing on months of precise measurements taken from two young male models. From these observations, he developed an empirical system of body proportions, which led him to slightly adjust Vitruvius’s original claims. Leonardo never accepted received wisdom without question—his work was fueled by a brilliant, childlike creativity and insatiable curiosity.

The Renaissance was fundamentally concerned with ideals. But Ceroli’s three-dimensional sculpture suggests how unstable and fragile these ideals can become when projected from theory into the messy reality of human life—when the “perfect two-dimensional man” must inhabit a three-dimensional world. The result is something like a puppet, hanging by threads. To create, to realize ideals, requires courage and openness—and imbalance is often inevitable, much like in the course of travel. Placing this piece in an airport is a striking gesture: travelers pass by it as they themselves move through transitional space, using the sculpture—like Leonardo’s work itself—as a meeting point and reference in motion.