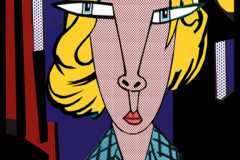

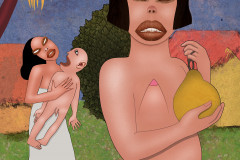

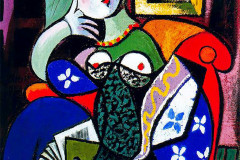

Wesselmann, Tom (1931-2004): Cigiző 1 (Száj 12), 1967 (olaj, vászon, 277 x 216 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York). A kezdetben képregényrajzolóként dolgozó amerikai pop-art művész alkotásai a női test és a szexualitás témája körül forogtak. A '60-as évek végén – '70-es évek elején alkotta meg híres cigarettás sorozatát, mely hatalmas női szájakat ábrázol füstölgő cigarettával. A Ruben Brandtban a tokiói pop-art-kiállításon tűnik fel a sorozat egyik darabja.

Wesselmann a '60-as évek első felének „Nagy amerikai akt”-sorozatától jutott el a női testrészek, jellemzően mellek és ajkak önálló ábrázolásáig, a női test személyiségtől megfosztott tárgyiasításában még egy lépéssel továbbhaladva. A vérvörös, érzékien nyíló ajkak és hófehér fogak hozzák a reklámok „szexi nő”-ábrázolásának kliséit, csak éppen itt nem valaminek az eladása a cél, hanem önmagukért jelennek meg az erotikus elemek. A nagyítás, sematizálás, a frontálisan „telibe” elénk helyezés azonban mind-mind olyan elidegenítő eszközök, amelyek inkább fenyegetővé, mintsem finoman csábítóvá teszik a motívumot. (Ez a ránagyítás, nagyobb összefüggésből, képből való kiemelés olyan eszköz, amellyel a Ruben Brandt animációja is gyakran él, pl. a „képek támadásaikor”).

A cigaretta labilis helyzete bizonytalanságot kelt, összezavarja érzékelésünket, mintha a következő pillanatban már ki is esne a szájból, vagy mintha egy hamutartón támaszkodna fordítva az alsó ajkon, így is a tárgyszerűséget erősítve. Wesselmann ennél a művénél is alkalmazza a „Nagy amerikai akt”-sorozatban kifejleszett „több vásznas módszert”: az alkotás valójában két részből áll, a cigaretta füstje egy a hátsó vászon elé helyezett, formára vágott különálló darab. Ezzel a megoldással a festő fricskát mutat a festészet tradicionális térábrázolási törekvéseinek, s frappánsan megoldja a három dimenzió megjelenítését.

Wesselmann, Tom (1931–2004): Smoker 1 (Mouth 12), 1967

(oil on canvas, 277 x 216 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York)

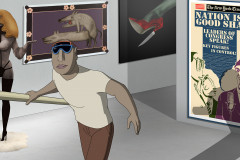

The American pop artist—who began his career as a cartoonist—was best known for his provocative explorations of the female body and sexuality. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Tom Wesselmann created his famous Smoker series: monumental images of glossy, red-lipped mouths sensually holding a smoking cigarette. One of these striking works appears in Ruben Brandt, Collector at the Tokyo pop-art exhibition.

Wesselmann’s journey from his Great American Nude series to the isolated depiction of female body parts—most often lips and breasts—marks a further step in the objectification of the female form. In Smoker 1, the glossy red lips, bright white teeth, and thick smoke channel the visual language of commercial seduction, evoking the clichés of advertising’s “sexy woman.” But unlike an ad, these features serve no product—they exist entirely as image, as amplified erotics turned inwards on themselves.

Yet the image is more alienating than alluring. The monumental scale, schematic treatment, and direct, frontal composition create a sense of confrontation rather than seduction. The lips are no longer part of a face or body—they are decontextualized, magnified, and unsettling. This kind of visual isolation and enlargement is mirrored in Ruben Brandt, Collector, particularly during the "art attacks," where artworks come to life and disorient characters with sudden, exaggerated closeness.

The cigarette itself adds tension. Its ambiguous position—balancing precariously on the lower lip, almost upside down—destabilizes the viewer’s perception. Is it about to fall? Is it propped there unnaturally like a prop in a showroom? The ambiguity turns the mouth from a sensual object into something surreal, even absurd.

Technically, Wesselmann’s innovation here echoes his Great American Nude compositions: Smoker 1 is made using a multi-canvas technique. The smoke is rendered on a cutout canvas that sits in front of the main painting—breaking with traditional illusionistic depth in favor of a sculptural, three-dimensional effect. It’s a clever pop-art rebuttal to the history of perspective in painting, turning space into object and flat image into layered experience.

Much like the film it appears in, Wesselmann’s Smoker 1 walks the line between attraction and disturbance, using familiar symbols in strange, dissected ways that make us question what exactly we’re seeing—and why we’re drawn to it.