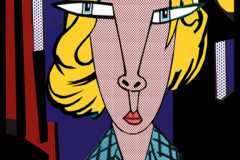

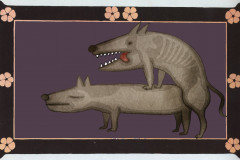

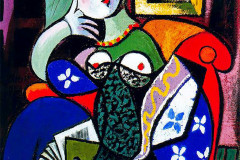

Chirico, Giorgio de (1888-1978): Nyugtalanító múzsák, 1916-18 (olaj, vászon, 97 x 66 cm, Gianni Mattioli magángyűjteménye, Milánó). A Görögorszában született olasz festő az 1910-es években összetéveszthetelenül egyedi stílust alakított ki, melyet ő maga metafizikus festészetnek nevezett, s amely később a szürrealistákra is nagy hatást gyakorolt. Ruben Brandt Firenze utcáit rója álmában, amikor egy „Chirico-városrészben” találja magát, amelynek feszültségteli hangulata jól passzol a belevegyülő Hopper-képrészletekhez.

Mi az, hogy „metafizikus”? A valóságos fizikai világon túlmutató, a tárgyak és emberek pillanatnyi megjelenésétől független „lényegre” fókuszálás. A művészetnek persze mindig is volt olyan szándéka, hogy ne csak a láthatót érzékeltesse (az egész vallásos művészet ennek a szándéknak jegyében születik), de pont a 19-20. sz. fordulóján számos művész volt a „pillanatnak” elköteleződve (ld. impresszionisták, futuristák). De Chirico velük ellentétben a mozdulatlanság, időtlenség festője. Az első világháború mindent felforgató, kaotikus időszakában számára a festészet lehetőség a felülemelkedésre, a kilépésre az éppen összedőlni látszó fizikai világból. A korabeli avantgárd művészet központjából, Párizsból visszavonulva Ferrarában telepszik le, a festményein szereplő épületek, terek e város kulisszái. Ebben a világban az élő embereket szobrok, vagy bábuk helyettesítik, melyek olykor meglepő tárgyakkal társítva, precízen elrendezve állnak – nem tudjuk mi célból, mióta és meddig még. A „nyugtalanság” e csönd ellenére azonban mintha minden képben benne lenne: egyik oka a perspektíva, azaz térábrázolás különleges használata, a nézőpontok keverése, nem mindent ugyanabból a szögből látunk, ezáltal mintha kissé kihúznák a lábunk alól a talajt: rend van, de nem értjük milyen…

Chirico, Giorgio de (1888–1978): The Disquieting Muses, 1916–18 (oil on canvas, 97 x 66 cm, Gianni Mattioli Private Collection, Milan). Born in Greece, the Italian painter developed a distinctly unique style in the 1910s, which he called metaphysical painting—a term that would later have a major influence on the Surrealists. In Ruben Brandt, Collector, the protagonist wanders the streets of Florence in a dream, eventually finding himself in a “Chirico-district,” its charged, eerie atmosphere blending seamlessly with fragments of Hopper’s imagery.

What does “metaphysical” mean? It refers to something beyond the physical world—an attempt to focus on an essence that transcends the immediate appearance of people and objects. Art has long aimed to represent more than what is visible (religious art, for example, was largely born from this intention), but around the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, many artists were devoted to capturing fleeting moments (think Impressionists, Futurists). De Chirico, in contrast, became the painter of stillness and timelessness. Amid the chaos and upheaval of World War I, painting became for him a means of transcendence—a way to escape a physical world that seemed to be collapsing. Retreating from the epicenter of avant-garde art in Paris, he settled in Ferrara, where the buildings and spaces of his paintings draw on the city’s real backdrops.

In this world, living humans are replaced by statues or mannequins, often paired with unexpected objects and arranged with surgical precision. Their presence is puzzling—we don’t know their purpose, how long they’ve been there, or how long they’ll remain. And yet, despite the silence, there’s a palpable sense of unease in every image. One reason lies in his use of perspective—De Chirico blends different viewpoints within a single frame, so not everything is seen from the same angle. The result is subtly destabilizing: there’s order, but we can’t quite grasp its logic.