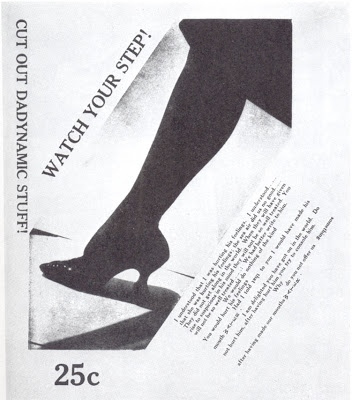

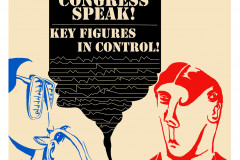

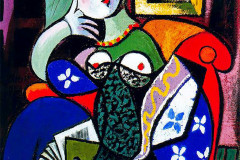

New York Dada (szerk. Marcel Duchamps, Man Ray): Watch Your Step! 1921 Az Európából elsősorban Marcel Duchamp közvetítésével az USÁ-ba került dadaista mozgalom egyetlen számot megért folyóiratának, a New York Dadának egy lapja, mely az egyik legmeghatározóbb amerikai fotográfus, Alfred Stieglitz 1919-es fényképének feliratokkal ellátott változata. A Ruben Brandtban a tokiói pop-art-kiállításon tűnik fel a képet átlósan átszelő női láb, amelynek élét a harsány piros szín és a cipősarok helyén lévő kés fokozza. A piros magassarkú – hol csupán hangsúlyozottan nőies, hol támadóan agresszív - motívuma egyéb helyeken is előkerül a filmben: pl. a léghajón telefonáló, s közben lábát himbáló Mimin vagy Manet Olympiáján, aki a képből ki is rúgja Rubenre piros topánját.

A magazinoldal alapját képző szürrealisztikus fotó a véletlenül műve: Stieglitz egymásra exponált két képet, egy hagyományos, arcát szemből mutató portrét felesége, Georgia O'Keeffe barátnőjéről, Dorothy True-ról és egy ugyanennek a hölgynek az egyik lábát rafinált, geometrikus kompozícióba foglaló képet. A modern nő portréjának is felfogható fotót használták fel aztán a New York Dada szerkesztői a '20-as években divatos női magazinok paródiájaként is értelmezhető kiadványukban. A nőt csak térdtől lefelé mutató kép a harisnya- és cipőreklámok fotóit idézi, a „Watch Your Step!” („Vigyázz, hova lépsz!”) felirat azonban a hölgyeket óvó tanácsokkal ellátó rövid kis cikkek címeire hajaz, de közben vicces képi-nyelvi játékkal utal a „láb-képen” átütő portré tekintetére. A kép jobb alsó sarkában egy kissé összefüggéstelen, romantikus novellák kliséit tartalmazó szöveg olvasható: férfi-női kapcsolat, megbántás, s hasonló motívumok vehetők ki a sorokból, melyekkel a kissé agresszíven „odalépő” női láb szintén kapcsolatba hozható. A dadaizmusra jellemzően megvan a szabadságunk újabb és újabb jelentések konstruálására és mindennek az ellenkezőjére is.

New York Dada (ed. Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray): Watch Your Step!, 1921

This image—a page from the sole issue of the Dadaist magazine New York Dada—was created by two of the movement’s leading figures, Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray. It features a modified version of a 1919 photograph by the influential American photographer Alfred Stieglitz. In Ruben Brandt, Collector, a stylized homage appears at the Tokyo pop-art exhibition: a dramatically angled female leg slices across the frame, tipped with a stiletto heel turned into a knife. The striking red high heel—at once a symbol of femininity and potential aggression—recurs throughout the film: swaying on Mimi’s foot as she makes a call aboard an airship, or even flying from Manet’s Olympia as she literally kicks her shoe at Ruben.

The photograph at the heart of Watch Your Step! was itself the result of chance—an accidental double exposure by Stieglitz. One shot was a front-facing portrait of Dorothy True, a friend of Stieglitz’s wife Georgia O’Keeffe; the other, a more stylized composition focusing solely on True’s leg, positioned within sharp, geometric framing. The resulting image—a fragmented but strangely cohesive representation of the “modern woman”—was later adopted by Duchamp and Man Ray as the visual centerpiece of New York Dada, a tongue-in-cheek parody of fashionable women’s magazines of the 1920s.

The visual irony is rich. A leg, cut off at the knee, evokes the familiar language of hosiery and footwear ads, but here it’s loaded with menace. The headline, “Watch Your Step!”, parodies the moralizing advice columns of the time while winking at the viewer: the gaze of the portrait—barely visible beneath the leg—turns the table, making the viewer the object. In the lower right, a block of loosely connected, clichéd romantic prose (“he had hurt her, but she…”) adds another layer, evoking pulp fiction and emotionally overwrought magazine stories, which the aggressive female leg now seems to trample.

Like much of Dada, Watch Your Step! revels in contradiction, nonsense, and playful provocation. It invites endless reinterpretation—and reversal. In Ruben Brandt, Collector, this spirit lives on. The film blends art-historical reference and psychoanalysis, letting feminine allure and danger walk—sometimes literally—hand in hand.