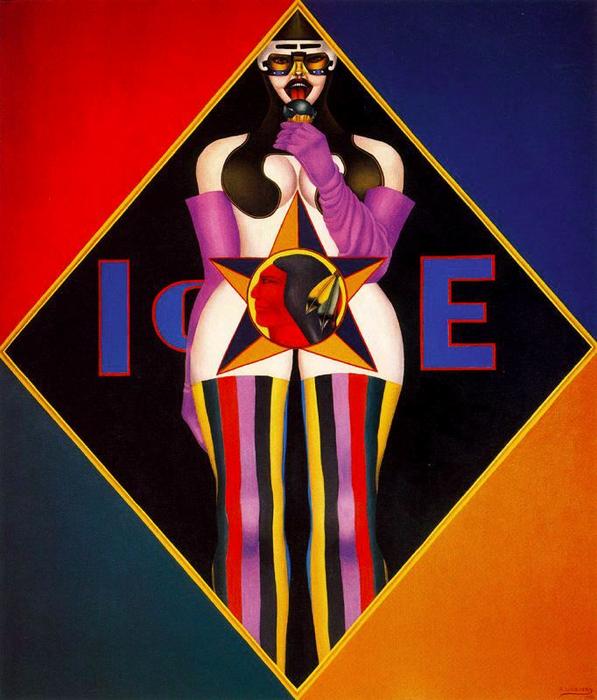

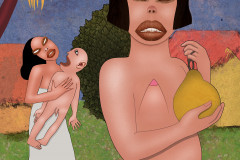

Lindner, Richard (1901-1978): Ice (Fagylalt), 1966 (olaj, vászon, 177,8 x 152,6 cm, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York). A német származású amerikai pop-art művész a reklám- és könyviparban dolgozott alkalmazott grafikusként, illusztrátorként, s képzőművészettel csak az '50-es évek elején kezdett komolyan foglalkozni New Yorkban. Stílusát mechanikus kubizmusnak is szokás nevezni, a kemény, geometrikus képi világa miatt, melyben robotszerűvé stilizált, gyakran erotikus utalásoktól sem mentes női alakok jelennek meg. A Ruben Brandtban a tokiói pop-art-kiállításon a film állandó turistapárja, George és Margaret ácsorognak a képnél, a „performansz” kezdetekor.

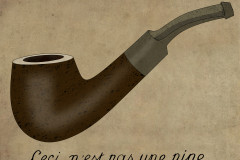

Mint egy jelvény vagy absztrakt embléma van megszerkesztve a sarkára állított rombusz által teljesen szimmetrikusan, élénk színes képmezőkre osztott kompozíció, amelynek középtengelyében áll a bizarr ruházatú nőalak. Alakja kerek csípőjével, gömbkebleivel egyszerre hat erotikusan, hangsúlyozottan nőiesen és életidegenül, gépiesen mereven. Frontális, szinte teljesen szimmetrikus alakja, mint valami archaikus istennő vagy idol emelkedik előttünk. A fagylaltnyalás látványos gesztusa azonban lerántja ezekből az elvont magasságokból a nőalakot, akinek már-már értelmezhetetlenül abszurd a megjelenése a csíkos harisnyában, vállig érő kesztyűben és robotszemüvegben. Teste középpontját, hasát és nemiszervét egy indiánférfi profilképmása takarja. Amerika ősi kultúrájának férfija és modern, média-irányította világának nője? Nem kicsi a kontraszt.

Lindner, Richard (1901–1978): Ice, 1966 (oil on canvas, 177.8 x 152.6 cm, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York). A German-born artist who became a key figure in American pop art, Lindner began his career in commercial illustration and book design. He only turned seriously to fine art in the early 1950s, after settling in New York. His unique visual language—sometimes called "mechanical cubism"—is marked by hard-edged geometry and robotic, often erotically charged, stylized figures, especially women. In Ruben Brandt, Collector, the painting appears during the Tokyo pop-art exhibition, as the ever-present tourist couple George and Margaret pause before it—just moments before the “performance” chaos begins.

The composition of Ice resembles a badge or abstract emblem: a diamond-shaped canvas tilted on its point, divided into vivid color fields with perfect symmetry. At its vertical axis stands a surreal female figure—outfitted in eccentric, fetishized garments. Her curvy hips and round breasts suggest femininity and allure, yet her posture and expression are rigid, cold, and artificial, like a machine or doll. She gazes straight ahead in full frontal view, evoking an idol or archaic deity. But the dramatic gesture of licking an ice cream cone pulls her abruptly back from that mythical realm into a pop-cultural one.

Her appearance verges on absurd: striped stockings, elbow-length gloves, visor-like goggles. The figure’s center—her abdomen and genital area—is obscured by the profile image of a Native American man. It’s a jarring insertion. The juxtaposition of Indigenous American masculinity and media-shaped Western femininity suggests a stark cultural and ideological contrast—between the primal and the artificial, the historic and the hypermodern.

Lindner’s work plays with objectification, spectacle, and power. In Ice, female sexuality is not so much liberated as mechanized—trapped within coded gestures and commercial styling. Just as Ruben Brandt, Collector explores how media imagery shapes identity, memory, and desire, Lindner’s painting invites viewers to examine how femininity is packaged, posed, and consumed. The message is unclear, even disturbing—but intentionally so. It's satire and fetish, monument and parody—all in one electric, frozen frame.