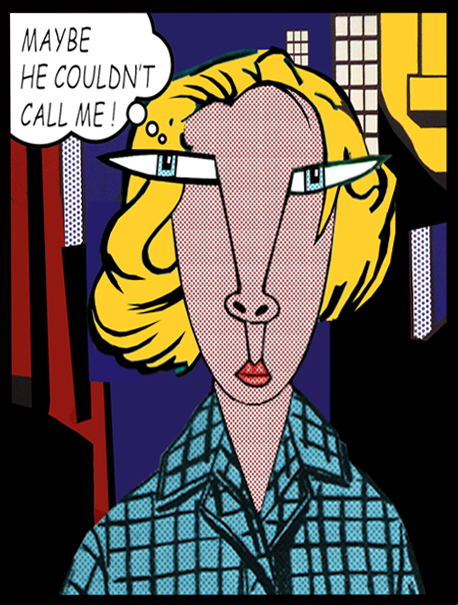

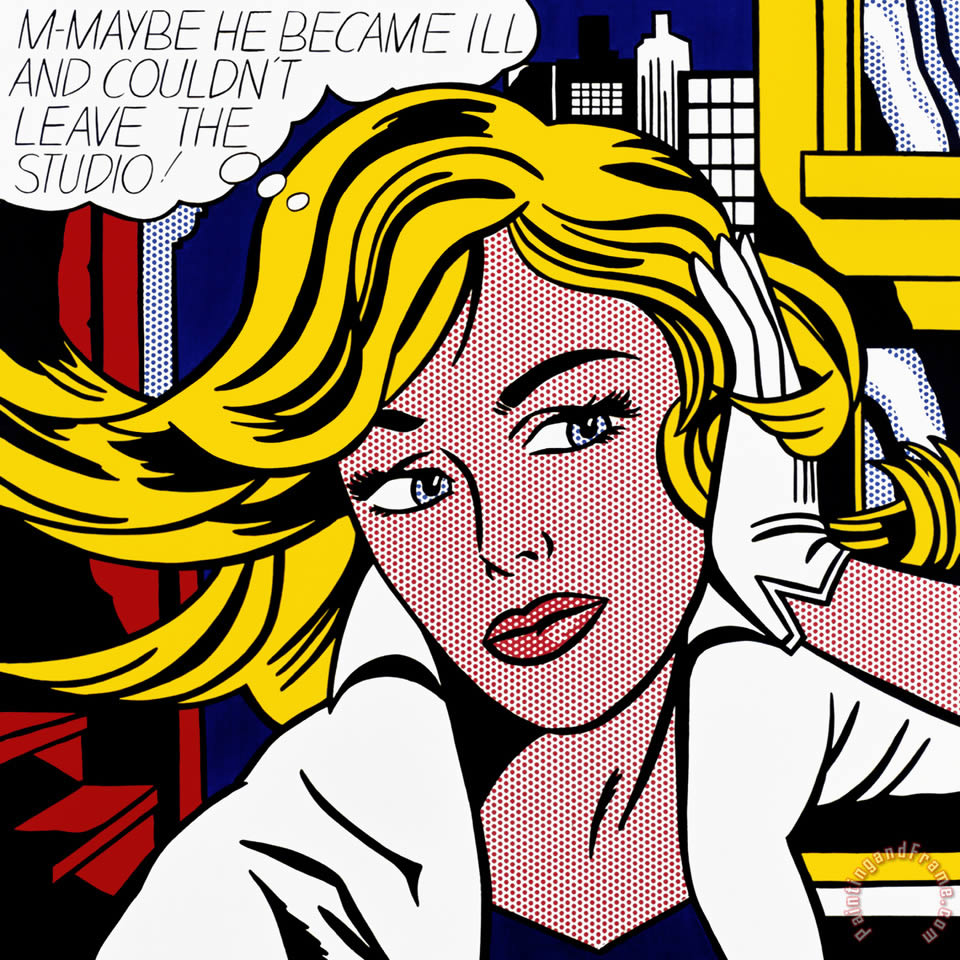

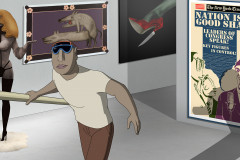

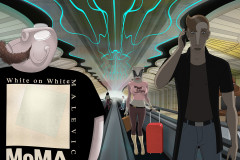

Lichtenstein, Roy (1923-1997): T-talán (M-maybe), 1965 (olaj, vászon,152,4 cm x 152,4 cm. Museum Ludwig, Köln). Az amerikai pop-artnak Andy Warhol mellett legnagyobb hatású alkotója képregénykockák felnagyításával teremtett sajátos – szándéka szerint személytelen, mechanikus stílusú, de mégis összetéveszthetelenül egyedi képi világot. A filmben jó pár Lichtenstein-művel találkozhatunk a tokiói pop-art-kiállításon.

„T-talán beteg lett és nem tudott eljönni a stúdióból”- olvashatóak a szövegbuborékban az aggódó arcú szőke szépség gondolatai. De valljuk meg, mi is és a lány is tudja, hogy ez nem igaz: a romantikus képregények férfihősei nem szoktak megbetegedni, valószínűleg más okból hagyják cserben a nőket – akik kiszolgáltatottan, érzelmesen, sokszor könnyes szemmel várják a férfit. Lichtenstein előszeretettel ragadja ki a képregénykockák folyamából ezeket a szentimentális pillanatokat, amelyeket a ponyva- és képregények olvasói halomszámra „fogyasztanak”. Így felnagyítva, a sztoriból kiragadva azonban váratlan jelentőségre, komolyságra tesznek szert. Irónia, de tisztelet is árad ezekből az ábrázolásokból. „Vizuális méltóság” - olvashatjuk egy elemzésben. „Formát teremtek a képregények formátlanságával szemben”- mondja Lichtenstein. Ez a forma pedig vállaltan egyszerű, letisztult és precíz. Lichtenstein a hideg klasszicista a pop-artosok között.

Lichtenstein, Roy (1923–1997): M–Maybe, 1965 (oil on canvas, 152.4 cm x 152.4 cm, Museum Ludwig, Cologne). Alongside Andy Warhol, Lichtenstein was one of the most influential figures of American pop art. By enlarging comic book panels, he created a distinctive visual world—deliberately impersonal and mechanical in style, yet unmistakably unique. In the film, several of his works appear at the Tokyo pop art exhibition.

“M–maybe he became ill and couldn’t leave the studio,” reads the thought bubble of the worried blonde beauty. But let’s face it: both we and the girl know it’s not true. The male heroes of romantic comics don’t get sick—they abandon women for other reasons. And the women, helpless and emotional, often wait tearfully for them to return. Lichtenstein often extracts these sentimental moments from the comic book flow—scenes that pulp and comic book readers consume in droves. When enlarged and removed from their original context, however, these moments gain unexpected weight and seriousness. There is irony, but also respect in these portrayals. As one analysis puts it: “visual dignity.” Lichtenstein himself said: “I bring form to the formlessness of comics.” This form is intentionally simple, clean, and precise. Among the pop artists, Lichtenstein is the cold classicist.