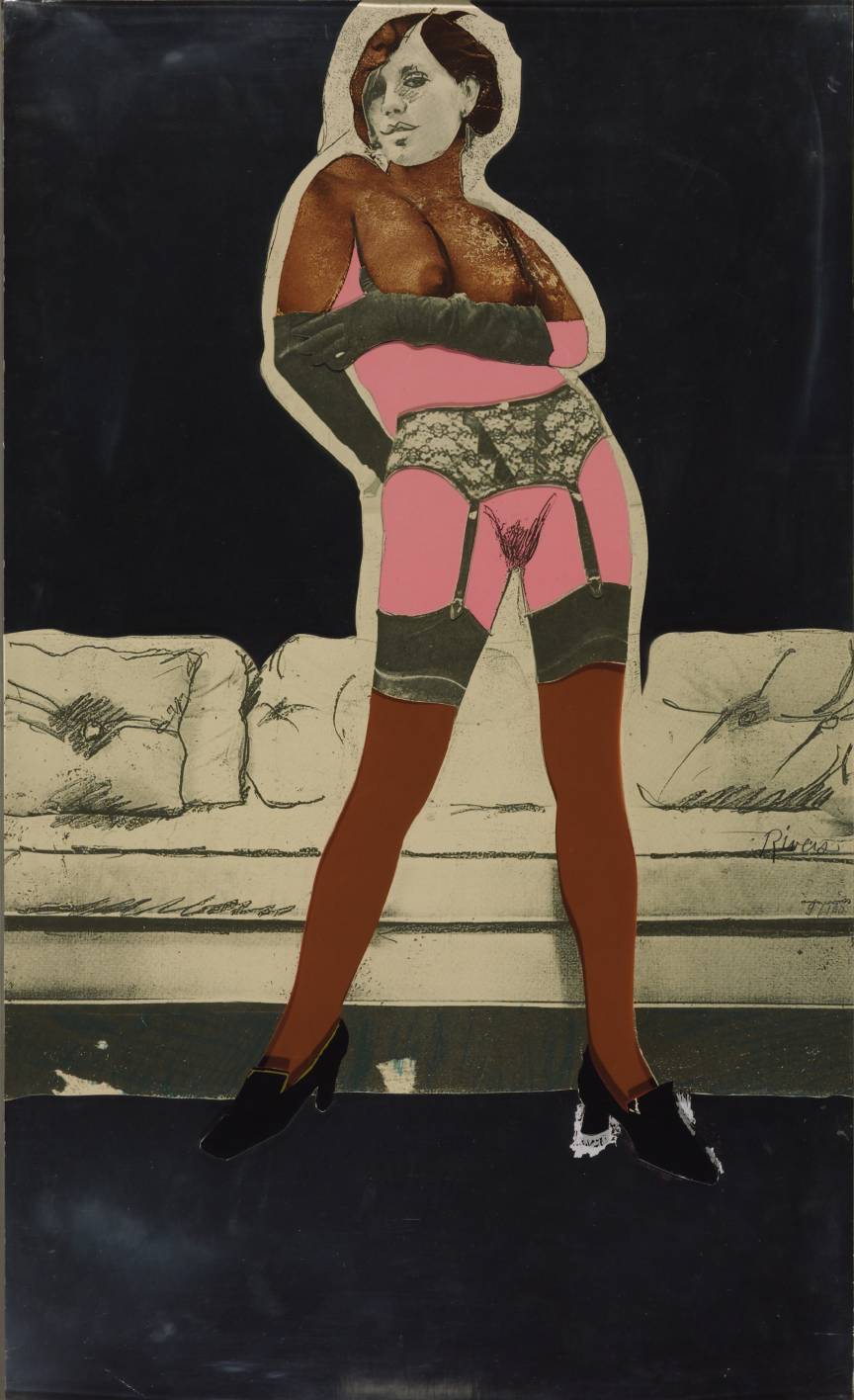

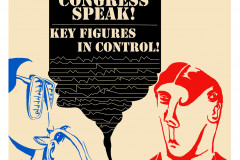

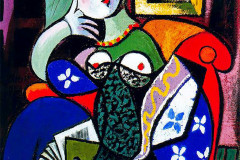

Rivers, Larry (1923-2002): Girlie (Csaj), 1970 (szitanyomat, kollázs, fémes papír, 75,6 x 45,7 cm, Tate Gallery, London). Az amerikai képzőművész, jazz-zenész, filmrendező és alkalomadtán filmszínész már a pop-art irányzatának kezdeteinél jelen volt a New York-i művészeti életben, az elsők között használta fel a kommersz, fogyasztói kultúra tárgyait (pl. csomagolásokat, bankjegyeket) alkotásaiban. Girlie c. képének átalakított verziója a tokiói pop-art-kiállításon tűnik fel, ahol a lány kihívó gesztusa inkább rémületre változik, ami nem csoda, ha figyelembe vesszük micsoda „performansznak” a tanúja.

Az absztrakt expresszionizmusban iskolázott Rivers figurális műveiben is mindvégig megőrizte a „művész keze nyománt”, személyes gesztusait őrző expresszív ecsetkezelést és rajztechnikát. Ő sosem lett az a fajta pop-art-művész, aki örömmel elmerül és válogat a média által sematizált és mechanikusan előregyártott képelemek között. Témái közt előkelő helyet foglal el a szexualitás, annak tabudöntögető, határsértő megjelenítése (pl. tinédzser lányainak testi változását dokumentáló videók, melyek a lányok tudta nélkül készültek, ezért ők meg is tiltották azok publikálását). „Girlie” c. művén a háttér vázlatosan felskiccelt kanapéja előtt kollázsként jelenik meg a cipőben, harisnyában és kesztyűben, fehérnemű nélkül, nyíltan felkínálkozó pózban álló lány. A közeli nézőpont, a csábítóan ránk irányuló tekintet nem engedi, hogy félrenézzünk, kitérjünk előle. A barna-rózsaszín-fehér bőrrel való játék, a különböző színű felületek váltakozása „szétszedi” a testet és a látványt, elbizonytalanít, hogy mit is látunk: meztelenséget vagy ruhaanyagot, fekete vagy fehér lányt, hús-vér nőt vagy papírdarabokból összeragasztott „plakátlányt”?

Rivers, Larry (1923–2002): Girlie, 1970 (screenprint, collage on metallic paper, 75.6 x 45.7 cm, Tate Gallery, London). One of the early figures in New York’s pop-art scene, Larry Rivers was also a jazz musician, filmmaker, and occasional actor—an artist of many talents who helped shape the emerging visual language of postwar American art. His Girlie appears in altered form in Ruben Brandt, Collector, during the Tokyo pop-art exhibition, where the figure’s provocative pose shifts into one of shock—a fitting reaction to the chaotic “performance” she witnesses.

Though trained in abstract expressionism, Rivers never abandoned the raw, expressive energy of gesture. Even in his figurative works, the artist’s hand is always present—loose lines, painterly textures, and sketched outlines retain an emotional immediacy. Unlike many pop artists who embraced slick, impersonal imagery from mass media, Rivers used commercial culture’s icons with irony, resistance, and critical distance.

Sexuality was a recurring—and controversial—theme in his work. He often explored it provocatively, even transgressively, as in the case of personal videos documenting the physical development of his teenage daughters, which were made without their knowledge and later withdrawn from public view at their request.

In Girlie, a stylized young woman appears before a loosely drawn couch, collaged directly onto the metallic background. Wearing high heels, stockings, and gloves—but no underwear—she assumes a blatantly suggestive stance. Her gaze confronts the viewer directly; it’s impossible to ignore her. Rivers plays with shades of brown, pink, and white, interspersing painted and printed surfaces in ways that fragment the body. This visual dissonance—between flesh and fabric, black and white, real and artificial—undermines clarity. Are we seeing nudity or clothing? A Black or white girl? A living figure or a paper-doll pin-up?

The ambiguity forces us to question what we’re really looking at—just as Ruben Brandt, Collector encourages us to interrogate the images we consume. Like Rivers’ Girlie, the film complicates desire, media spectacle, and the line between reality and representation, turning pop culture into a field of psychological tension.