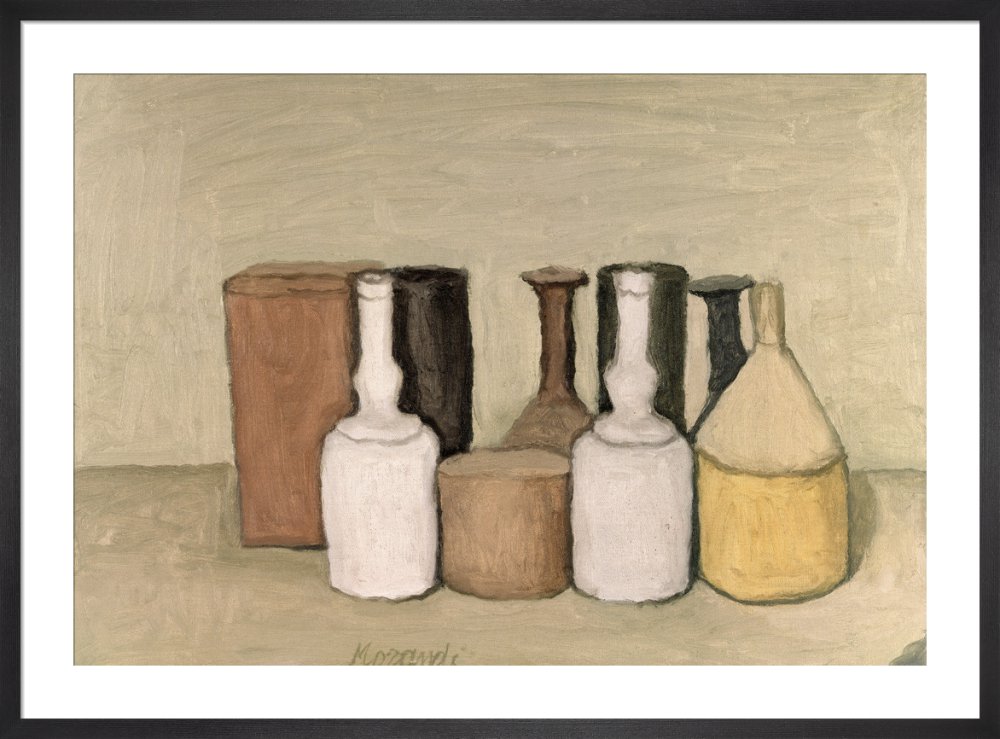

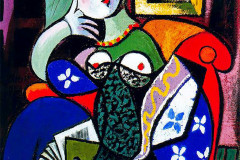

Morandi, Giorgio (1890-1965): Csendélet, 1953 (olaj, vászon, 30 x 43 cm), Pinacoteca Comunale di Faenza. A szinte egész életében csendéleteket festő olasz művész a mozgást és dinamikát istenítő futurizmus és a mindent felforgató első világháború után visszatérő klasszikus értékeket, statikus, valóban „csendes” világot jeleníti meg műveiben. A Ruben Brandtban a Cold War Bar pultosa mögött sorakoznak az üvegek a Morandira jellemző színvilágban és rendben.

Az 1910-20-as évek rendkívül izgalmas, átalakulásokkal teli időszakában nemcsak a politikában, hanem a művészetben is folyt a rendre és rombolásra törekvők küzdelme. Ugyanaz a Carlo Carrà például, aki 1909-ben még a minden régi művészet lerombolását követelő futurista kiáltványt írta alá, 1918-ban már az olasz „Novecento” néven formálódó klasszikus irányultságú csoport nevében fogalmazott: „Azt akarjuk, hogy az itáliai festészet visszataláljon a rendhez, a módszerességhez és a fegyelemhez, s szilárd, tapintható formákat alkalmazzon”. Morandi művészete mintha ezeknek az elveknek a megtestesülése lenne. Diákkorától kezdve a csendéletek kötötték le figyelmét, a klasszikus reneszánsz festők és Cézanne nyomdokain haladva alakította ki saját stílusát. Gondosan kiválasztott üvegei és tálkái, jelzés nélküli, csak az asztallap széle által osztott sejtelmes-homályos térben jelennek meg. Visszafogott színekkel megfestett, finom, sohasem teljesen egyenes, sötét kontúrokkal körbefogott formái végtelenül leegyszerűsítve, mégis lélekkel telve ábrázolják a leghétköznapibb tárgyakat.

Morandi, Giorgio (1890–1965): Still Life, 1953 (oil on canvas, 30 x 43 cm, Pinacoteca Comunale di Faenza). The Italian painter, who devoted nearly his entire career to still life, created a quiet, static world in his work—one that stood in deliberate contrast to the dynamism of Futurism and the upheaval of World War I. In Ruben Brandt, Collector, bottles arranged behind the bartender in the Cold War Bar echo Morandi’s restrained palette and signature compositional order.

The 1910s and ’20s were a time of intense artistic and political transformation, marked by a clash between forces of order and destruction. Carlo Carrà, for instance, who in 1909 had signed the Futurist manifesto calling for the demolition of all old art, was by 1918 advocating for a return to classical values through the Novecento movement: “We want Italian painting to return to order, method, and discipline, and to use solid, tangible forms.” Morandi’s art seems to fully embody this ethos. From his student years onward, he focused on still life, developing a style grounded in the legacy of the Renaissance masters and Cézanne.

His carefully chosen bottles and bowls appear in a vague, muted space divided only by the edge of a tabletop. Painted in subdued tones, the objects are surrounded by dark contours—never quite straight—and rendered with such simplicity and calm that even the most ordinary forms seem imbued with quiet emotion. Morandi’s compositions reduce the world to its essentials, offering a meditative stillness that reflects both discipline and deep introspection.