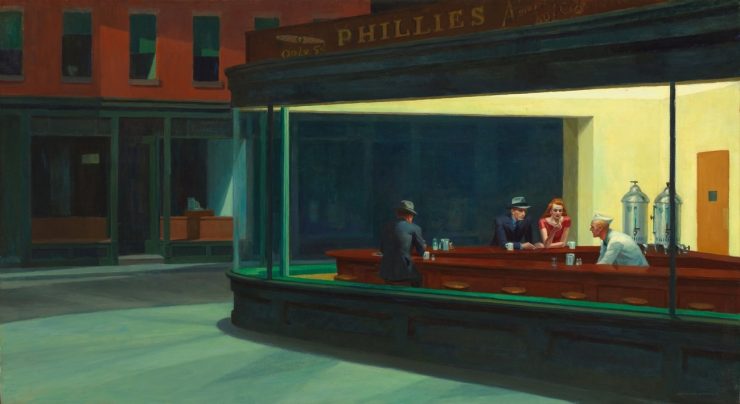

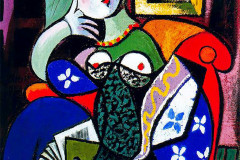

Hopper, Edward (1882-1967): Éjjeli baglyok, 1942. (olaj, vászon, 84 x 152 cm), Chicago Art Institut. Az amerikai realista festészet egyik legismertebb és legtöbbet idézett képe, amely a '40-50-es évek amerikai nagyvárosi hangulatának sűrítménye. Ruben Brandt 13 darabos kollekciójából sem hiányozhat a mű.

Az „éjjeli baglyok”, két férfi és egy nő, egy New Yorki-i utcasarkon álló éjszakai étterem vendégei – a festményt egy valós étterem ihlette, annak kinyomozására, hogy pontosan melyik, külön blog is alakult... Festészetileg mégis inkább a sötétség és fény kontrasztos játéka érdekes: ahogy a sötét, kihalt utcaképbe belevakít az étterem erős neonfénye, a hatalmas üvegablakokon át jól látható az egyetlen „esemény”: a kiszolgáló a vele szemben könyöklő, kalapos vendégre néz. Megállított, időtlen pillanat, feszült csend – Ruben Brandt rémálmában a vendég hátán mászó csiga csak még jobban fokozza ezt a feszültséget. Bejárat sehol – mintha üvegkalitkába lennének zárva a szereplők, Ruben Brandt kopogása sem ér el hozzájuk - a külvilágtól, de egymástól is el vannak szigetelve. „Alighanem – tudat alatt – a nagyvárosi magányt festettem meg.” - írta Hopper a képről, melynek nőalakjához felesége, Jo, a két férfivendéghez pedig saját maga ült modellt tükörből. Az éjszakai nagyvárosi hangulat, a kísérteties fények, az arcukba húzott kalapot viselő férfiak a 40-50-es évek amerikai „film noir”-ját, jellegzetes bűnügyi filmjeit is megidézik, melyeket a nagy mozirajongó Hopper jól ismert. A festmény maga is számos alkalommal megjelenik filmvásznon – nemcsak a Ruben Brandtban, hanem többek között, Daniel Argento A gonoszság áldozatai c. (1975) horrorklasszikusában, Ken Adams Filléreső c. (1981) musicaljében, Ralph Bakshi Csúcsforgalom c. (1973) egész estés animációs filmjében és Wim Wenders Az erőszak vége c. (1997) filmjében – itt ugyanúgy egy pisztoly eldördülésében robban ki a feszültség, mint a Ruben Brandtban. A festészetben is számos parafrázisa született a képnek, a legismertebbek Gottfried Helnwein Boulevard of Broken Dreams (1984) c. festménye, ahol hollywoodi filmikonok (Humphrey Bogart, James Dean és Marylin Monroe) ülnek Elvis Presley pultjánál, és Banksy 2005-ös Are You Using That Chair c. alkotása, ahol egy angol zászlóba burkolt huligán töri be az étterem ablakát – a Ruben Brandtban pedig ki? Emlékszel?

Hopper, Edward (1882–1967): Nighthawks, 1942

(oil on canvas, 84 × 152 cm, Art Institute of Chicago)

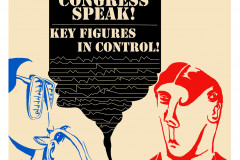

Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks is one of the most iconic works of American realist painting—a haunting portrait of urban solitude captured on a dimly lit New York street corner. A permanent fixture in pop culture and art history alike, the painting has inspired countless tributes, parodies, and reinterpretations—so naturally, it features among the 13 stolen masterpieces in Ruben Brandt, Collector.

Set in a late-night diner, the scene shows two men and a woman seated at the counter, along with the server. Hopper was reportedly inspired by a real restaurant in Greenwich Village—so much so that entire blogs have been dedicated to pinpointing its exact location. Yet it’s the emotional and visual atmosphere, not architectural fidelity, that makes the painting unforgettable. Bright, sterile fluorescent light floods the dark, empty street, and the towering glass window removes any separation between viewer and scene—except we’re still outsiders, looking in. And that’s the point.

There’s no visible door. The diner is like a sealed glass box. The figures are together, but not connected. Even in their physical proximity, they seem isolated—not just from the outside world, but from one another. Hopper himself admitted: “Unconsciously, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.” His wife Jo posed for the red-haired woman, while Hopper used his own reflection to model both male customers.

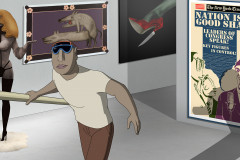

In Ruben Brandt, Hopper’s eerie stillness becomes even more unsettling. One of Brandt’s nightmares places him outside the diner, tapping in vain at the glass. The man inside has a snail creeping up his back—an uncanny, slow menace. As in the original, no one moves. No one notices. The neon lights and men in fedoras evoke classic American film noir—a genre Hopper knew well. That connection is reinforced by the fact that the painting has appeared in several films: Dario Argento’s Deep Red (1975), Ken Adam’s Pennies from Heaven (1981), Ralph Bakshi’s Heavy Traffic (1973), and Wim Wenders’s The End of Violence (1997)—where, just as in Ruben Brandt, tension explodes with the firing of a gun.

Nighthawks has also been revisited by countless artists. Gottfried Helnwein’s Boulevard of Broken Dreams (1984) famously replaced the diner’s anonymous patrons with James Dean, Marilyn Monroe, Humphrey Bogart, and Elvis Presley. Banksy’s Are You Using That Chair? (2005) added a British hooligan smashing the window with a chair.

And in Ruben Brandt? A woman does the honors—flinging a red high heel straight through the glass.

Does she look familiar? She should.