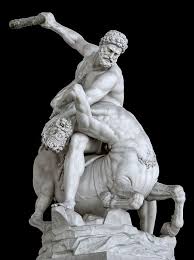

Giambologna (Giovanni da Bologna, 1524 k. - 1608): Herkules és Nesszusz, 1600 (márvány, 269 cm magas, Loggia dei Lanzi, Firenze). A firenzei főtéren álló nyitott csarnokban található a manierista szobrász mozgalmas alkotása a kor egyéb híres szobrai között. A firenzei nyomozásra érkező Kowalsky és Marina is elsétálnak előttük, bár ők nem a szobrokat nézegetik.

Az eredetileg flandriai származású szobrász csak 1-2 éves tanulmányútra érkezett Itáliába, de a hazafelé tartó úton megállt Firenzében, ahol szállásadója, egy gazdag művészetpártoló egyből felismerte tehetségét és igyekezett őt a városban tartani. Sikerrel: Giambologna hamarosan elismert művésze lett a városnak, s a Firenzét kormányzó Mediciek első számú szobrászaként számos megbízást elnyert. Stílusát meghatározza Michelangelo és a manierizmus hatása: az izmoktól duzzadó emberi testeket részletesen, anatómiailag hitelesen jeleníti meg, s bonyolult, mozgalmas kompozíciókba rendezi őket, ahol sokszor csak kapkodjuk a fejünket – melyik kinek a lába, keze, feje? Mi történik valójában? Herkules és Nesszusz vérre menő összecsapása kiválóan alkalmas a szenvedély és dráma megjelenítésére. A görög mitológia legerősebb félistene, Herkules száll itt szembe a feleségét révészként elrabló és majdnem megerőszakoló kentaurral, akit meg is fog ölni, de egy csel folytán a vérével átáztatott inge később majd Herkules halálát fogja okozni. Giambologna egyetlen márványtömbből faragta ki a hatalmas szobrot, s a tőle megszokott tömör, viszonylag kis teret kitöltő kompozícióba sűrítette bele a két alak rengeteg erőt (és erőszakot) megmozgató küzdelmét. A manierizmus által kedvelt és gyakran alkalmazott spirálban csavarodó testtartás, a „figura serpentinata” itt is megfigyelhető Herkules kentaurra lesújtó alakjában. A hős tekintete csak úgy villámlik, míg Nesszusz eltorzult, csukott szemű arcán látszik, hogy ő itt most már biztos vesztes – egyelőre. Mert a görög mitológiában senki sem kerülheti el sorsát, Herkulest is el fogja érni Nesszusz kései bosszúja.

Giambologna (Giovanni da Bologna, c. 1524–1608): Hercules and Nessus, 1600

(marble, 269 cm tall, Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence). This dynamic sculpture by the Mannerist master stands among other celebrated works in the open-air loggia on Florence’s main square. In Ruben Brandt, Collector, Kowalski and Marina walk past it during their investigation in Florence—though their focus is elsewhere, not on the sculptures.

Originally from Flanders, Giambologna came to Italy for a short study trip, but on his return journey he stopped in Florence, where a wealthy patron recognized his talent and convinced him to stay. It worked—he quickly rose to prominence, becoming the leading sculptor for the ruling Medici family and receiving numerous commissions. His style was shaped by Michelangelo and the ideals of Mannerism: muscular human forms rendered in precise anatomical detail, composed into complex, swirling arrangements that often leave viewers wondering whose limb belongs to whom—and what, exactly, is happening.

In Hercules and Nessus, the myth provides the perfect vehicle for depicting drama and emotion. The Greek demigod Hercules confronts the centaur Nessus, who attempted to abduct and assault his wife while pretending to ferry her across a river. Though Hercules kills him, Nessus’s blood-soaked tunic will later become the instrument of Hercules’s own death—a twist of fate the myth forewarns.

Carved from a single block of marble, the statue condenses the intense violence and physical struggle into a compact, almost explosive form. The spiral twist of the figures—figura serpentinata, a hallmark of Mannerist sculpture—is evident in Hercules’s raised body as he delivers the fatal blow. His gaze flashes with fury, while Nessus’s contorted, closed-eyed expression shows he knows he’s defeated—at least for now. In Greek mythology, no one escapes fate, and Hercules will ultimately fall to Nessus’s delayed revenge.