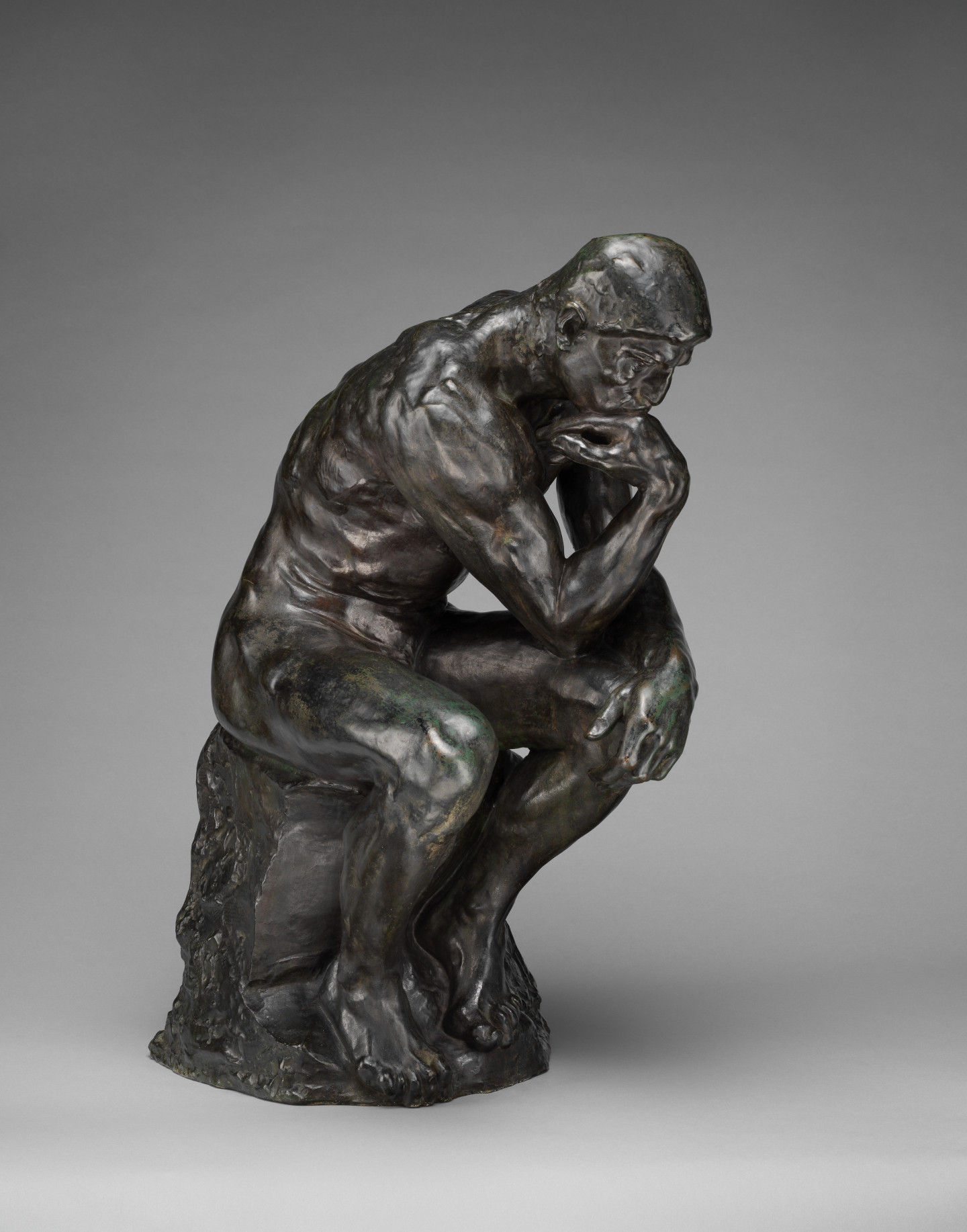

Rodin, Auguste (1840-1917): Gondolkodó, 1903, (bronz, 180 cm magas), Párizs Musée Rodin. Az impresszionizmushoz és szimbolizmushoz kapcsolódó francia szobrász talán leghíresebb műve, eredetileg egy soha be nem fejezett nagyobb mű, a Dante Isteni színjátékához készített Pokol kapujának felső figurája, amely aztán önállóan lett a világ egyik legismertebb szobra. A minden izmában a megfeszített koncentrációt tükröző testtartás segít Bye-Bye Joe-nak, hogy leküzdje problémáját: a rossz pillanatban való megszólalást – ezt aztán élőben is tesztelik az Olympia elrablásakor, amikor Gondolkodóként tud bent maradni a Musée d'Orsay-ben.

Te hogyan ábrázolnád a gondolkodást? Fekve, állva, sétálva? Látszik az a testen, hogy szellemi munkát végez? Rodin mozdulatlanul, de aktívan ülő, „kigyúrt” férfialakja egy pillanatra sem pihen: felső testével előre dől, jobb könyökével bal térdére támaszkodik, s így tartja fejét - ez a pici csavarodó mozdulat is hozzájárul a feszültséghez, amely az egész testben, s a ráncolt homlokú arcon is megjelenik. Ki lehet valójában ez a férfi? A mű első változatában, amely a kb. 6 méteresre tervezett bronzkapu (az akkoriban épülő párizsi Iparművészeti Múzeum kapujának szánva) tetején 70 cm nagyságban foglalt helyet, „A költő” megnevezést viselte, tehát az Isteni színjáték szerzőjét, Dantét láthatjuk benne. Vagy, ha kicsit elvonatkoztatunk - a Világot és a Poklot teremtő Istent? Alatta a mintegy 150 alakot számláló, rendkívül kaotikus kompozíción az emberiség vágyai, bűnei, szenvedései jelennek meg. Az alkotó teremtője, de kissé gondterhelt, tehetetlen szemlélője is művének. A kompozíciótól függetlenné vált Gondolkodó már a modern – Istentől elszakadt – ember szimbólumává is vált: saját gondolataival, belső küzdelmeivel felel saját világáért és életéért. Végül is a pszichoterápia is kb. ekkor születik meg, amikor ez a szobor. Tudjátok, amikor az ember változtatni akar saját magán – hát, ahhoz biztosan kell ekkora erő és koncentráció! Sok sikert, Bye-Bye Joe!

Rodin, Auguste (1840–1917): The Thinker, 1903

(bronze, 180 cm tall, Musée Rodin, Paris). The most iconic work of the French sculptor—who is linked to both Impressionism and Symbolism—The Thinker was originally part of a much larger composition, The Gates of Hell, inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy. Though that grand project was never completed, the seated figure at its top became one of the most recognizable sculptures in the world. In Ruben Brandt, Collector, the pose of intense, muscular concentration helps Bye-Bye Joe conquer his problem of speaking at the wrong moment—something he puts to the test while posing as The Thinker during the heist of Olympia at the Musée d'Orsay.

How would you portray the act of thinking? Lying down? Walking? Can intellectual effort show on the body? Rodin gives us a motionless yet intensely active figure: a muscular man leaning forward, right elbow on left knee, head resting in his hand. This subtle twist adds to the tension that courses through the body and is etched into his furrowed brow.

But who is this man, really? In its original version—perched atop the 6-meter Gates of Hell meant for the (never-built) Musée des Arts Décoratifs—the figure was only 70 cm tall and titled The Poet, representing Dante himself. Or perhaps he’s God—the creator of the world and hell—contemplating the chaos below, filled with 150 twisting, suffering figures. He is the maker, but also a troubled, helpless observer of his creation.

Once separated from that context, The Thinker became a symbol of modern humanity—cut off from divine authority, forced to wrestle with his own thoughts and take responsibility for his own world. Interestingly, psychotherapy was emerging around the same time as Rodin’s sculpture. When someone seeks to change themselves—it takes precisely this kind of strength and focus.

Good luck, Bye-Bye Joe. You'll need it.