Roman Polański lengyel rendező első nagyjátékfilmje pszichológiai „élveboncolás”, ahol nem a látványos képek, hanem a művészi komponálás és a színészi játék van előtérben. Egy fiatal nő és egy tehetős férfi viszonya háromszöggé nyílik, amikor a nyaralásukon felvesznek egy stoppost, majd a hajójukra is magukkal viszik. A fiatal stoppos és a nő között szimpátia és szenvedély lobban fel, a két férfi között pedig kitör a dominanciaharc.

A férfi középkorú, van egzisztenciája, befutott és híres. A srác fiatal, szegény és erős. Az egyiknek vitorláshajója van, a másiknak kése. A nőért versengve mindketten fitogtatják, amilyük van – egyikük az anyagi javait és a hatalmát, másikuk az ügyességét és vonzerejét. A Kés a vízben ezt a lélektani hadviselést mutatja be finom eszközökkel, és persze a házaspár kapcsolatának a szakítópróbáját is, rámutatva a kölcsönös függés, az összetartozás és a szexualitás kérdéseire.

És hogy mit keres a kés a vízben, illetve Kowalski nyomozó pengegyűjteményében? A Polański-film egyik központi motívuma a fiatal férfi kése, ami rosszat sejtetve újra és újra előkerül, majd a film egyik fordulópontján eltűnik a hajóról. Ez a kés több mint tárgy: egy kiélezett viszony szimbóluma. De az elnyomottságban ott rejlő fenyegetésé is. Nagyon is van keresnivalója a Ruben Brandt, a gyűjtő pszichothrillerében.

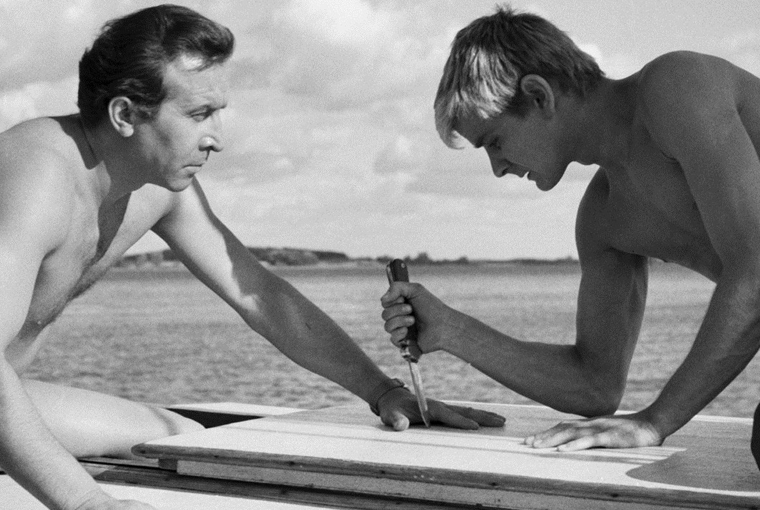

Polański úgy idézte fel a film keletkezését, hogy legelőször a víz, a lengyel tóvidék kezdte foglalkoztatni. Így találta ki ezt a „pokolian nehezen” leforgatható filmjét. A Kés a vízben legfőbb helyszíne ugyanis egy kis vitorláshajó, amin még a három főszereplőnek is alig jutott hely, nemhogy a stábnak. Ők hámokkal a hajóra erősítve lógtak, illetve egy másik hajóval lavíroztak a vitorlás mellett.

Az eredeti filmterv azt a kritikát kapta a korabeli filmes döntőbizottságtól, hogy nincs társadalmi relevanciája, ezért Polański beletett egy „szociálisan tudatos” párbeszédet – ironikus módon a film ágyjelenetébe. Így már gyártásba mehetett a Kés a vízben. Elkészültekor viszont pont azért nem kapott díszbemutatót Lengyelországban, mert a kommunista párt szerint társadalmi feszültségeket kelthetett volna; még akkor is, ha a hivatalos elmarasztalás szerint a filmben szereplő karakterek és helyzetek „egyáltalán nem tipikusak és relevánsak” Lengyelországra nézve. A film külföldi fogadtatása viszont annál elragadtatottabb lett: pszichológiai és társadalmi érzékenységét egyaránt dicsérték, és Bergmanhoz, Antonionihoz hasonlították a fiatal rendezőt.

Knife in the Water (dir. Roman Polanski, 1962)

Polanski’s first feature film is a psychological “vivisection,” where the focus isn’t on spectacle but on artistic composition and acting. A young woman and a wealthy man’s relationship turns into a triangle when they pick up a hitchhiker on their holiday and invite him onto their sailboat. A spark of sympathy and passion ignites between the young man and the woman, while a battle for dominance erupts between the two men.

The older man is middle-aged, wealthy, established, and famous. The younger man is poor, strong, and full of potential. One owns a sailboat, the other has a knife. As they compete for the woman, each flaunts what he has—one his material wealth and authority, the other his physicality and allure. Knife in the Water portrays this psychological warfare with subtle means, and at the same time puts the married couple’s relationship to the test, highlighting questions of mutual dependence, intimacy, and sexuality.

And what is the knife doing in the water—or in Detective Kowalski’s blade collection in Ruben Brandt, Collector? In Polanski’s film, the young man’s knife is a recurring object, always appearing with a hint of menace—until it mysteriously disappears from the boat at a pivotal moment. This knife is more than just a prop: it symbolizes a tense relationship, and the threat hidden within oppression. It certainly belongs in the psychological landscape of Ruben Brandt.

Polanski recalled that the idea for the film first came from water—the Polish lake region fascinated him. That’s how he conceived what he called a “hellishly difficult” film to shoot. Most of Knife in the Water takes place on a small sailboat, where even the three main characters barely fit—let alone the crew. The filmmakers worked harnessed to the boat, or maneuvered beside it in another vessel.

The original script was criticized by Poland’s film authorities for lacking social relevance. Polanski responded by inserting a “socially aware” dialogue—ironically, into the film’s bedroom scene. That satisfied the committee, and Knife in the Water was approved for production. Yet when it was finished, it didn’t receive a gala premiere in Poland because the Communist Party feared it might stir social tension—even though their official critique was that the characters and situations were “not at all typical or relevant” to Polish society. Abroad, however, the film was met with great acclaim: critics praised its psychological and social sensitivity, and the young director was compared to Bergman and Antonioni.