Mi történik, ha egy vámpír szerelmes? Hát, nem az, ami az Alkonyatban. A vámpírtematikát a világra szabadító Bram Stoker Drakula című regénye a 19. század végén sötétebb képet festett erről a hátborzongató szenvedélyről. Francis Ford Coppola thrillere pedig a dramaturgiai változtatások ellenére is a leghűségesebb adaptáció, ami a könyvből eddig született. Látvánnyal, effektekkel, fantasztikus kosztümökkel, vérrel és erotikával eléri, hogy fejest ugorjuk a történetbe, de közben magunkban mosolyogjunk is rajta.

Gyorsan vegyük át, hogy ki kicsoda a vámpírvilágban! Vérszívó lények szinte minden kultúra mítoszaiban vannak, de Drakula gróffal senki sem vetekszik ismertségben. Egyik előképének a 15. századi Vlad Tepes törökverő fejedelmet szokás tekinteni, akit ma Romániában nemzeti hősként tisztelnek, de például a szűzlányok vérében fürdő Báthory Erzsébet legendája is hozzájárult a történethez. Magát Drakula grófot Bram Stoker alkotta meg a kelet-európai folklórból és a saját fantáziájából. Nem ő találta fel a vámpírokat és messze nem ő írta az első vámpírregényt, de az ő levél-horrorja kövezte ki a vérszívók útját a világhír felé.

Bram Stoker egyébként egy londoni színházat vezetett a századfordulón, és a Drakulát csak szórakozásból és némi pénz reményében írta meg. A kortársai is inkább szórakoztató irodalomnak tekintették a művet – kultikussá a megfilmesítései tették. Mára több mint 200 Drakula-film született, de a nagy klasszikus akkor is F. W. Murnau Nosferatu című némafilmje maradt, 1922-ből.

Francis Ford Coppola 1992-es Drakulája is visszautal Murnau filmjére egy-egy beállítással és a film zenéjével. De az is a filmezés korábbi évtizedei felé mutat vissza, hogy egy fényhatáson kívül semmilyen, de tényleg semmilyen digitális trükköt vagy speciális effektust nem használt. Minden, amit a vásznon látunk, a felfele csepegő folyadéktól a farkasemberig: smink, maszk, kameratrükk, festmény és makett, ettől pedig érdekesen valóságos hatást kelt a film a CGI-hoz szokott szemünknek. Nem csoda, hogy mind a jelmez, mind a maszk Oscar-díjat kapott.

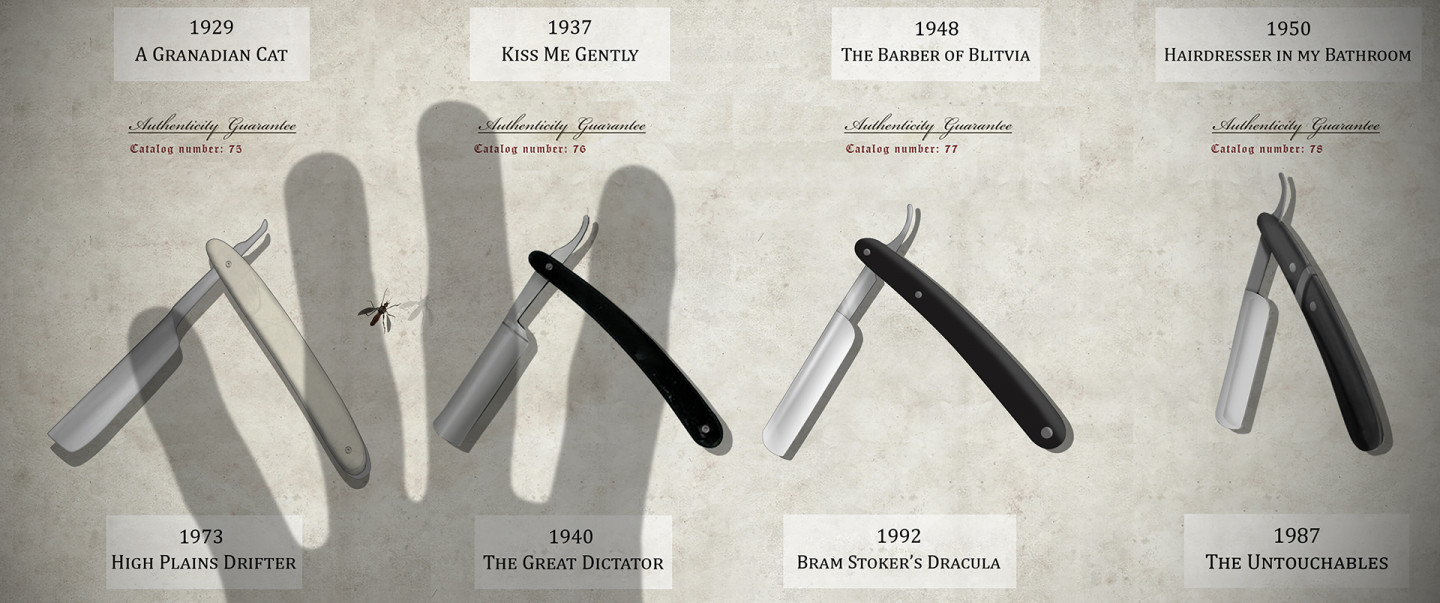

Coppola vámpírjai éppúgy megmentették a gyártó stúdiót a csődtől, mint korábban a Keresztapa című filmje. Hatalmas kasszasiker lett, de a kritikák főleg a kamerahasználatot és Gary Oldman játékát emelték ki. Magával ragadó látvány, operaszerű jelenetek, amiben a történetnél fontosabb az atmoszféra. A filmnek 1995-ben megszületett a paródiája is, a Drakula halott és élvezi. A Ruben Brandt, a gyűjtőbe pedig egy borotva révén került be, amelyről az éhes vámpír olyan kéjesen nyalja le a vért, hogy nem hiányozhatott Kowalski késgyűjteményéből.

Dracula (dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1992)

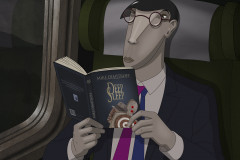

What happens when a vampire falls in love? Well, not quite what you see in Twilight. Dracula, the novel by Bram Stoker that unleashed vampire lore upon the world, painted a much darker picture of this chilling passion back in the late 19th century. Despite several dramatic changes, Francis Ford Coppola’s thriller remains the most faithful adaptation of the novel to date. With visual spectacle, effects, fantastic costumes, blood, and eroticism, the film pulls us headfirst into the story—though we may find ourselves smiling at it along the way.

Let’s quickly go over who’s who in the vampire world. Bloodsucking creatures appear in the myths of almost every culture, but none rival Count Dracula in fame. One of his possible prototypes is 15th-century ruler Vlad the Impaler, known for resisting the Turks and still revered as a national hero in Romania. The legend of Elizabeth Báthory, who allegedly bathed in the blood of virgins, also fed into the myth. But Count Dracula himself was born of Bram Stoker’s imagination, inspired by Eastern European folklore. He didn’t invent vampires, nor did he write the first vampire novel—but his epistolary horror paved the way for the bloodsucker’s rise to global fame.

Stoker, who managed a London theater around the turn of the century, wrote Dracula partly for entertainment and partly in hopes of some income. His contemporaries viewed it as popular fiction; it was the film adaptations that made it a cult classic. Over 200 Dracula films have been made to date, yet the silent film Nosferatu (1922) by F. W. Murnau remains the definitive classic.

Coppola’s Dracula (1992) also nods to Murnau’s film in its compositions and musical cues. It also gestures back to earlier decades of filmmaking through its total rejection of digital effects—except for one lighting trick, absolutely everything was done in-camera. From upward-dripping blood to the wolf-man, what we see on screen is makeup, masks, camera tricks, paintings, and miniatures. To eyes used to CGI, the result feels uncannily real. Unsurprisingly, both the costume design and makeup won Oscars.

Just like The Godfather once did, Coppola’s vampires saved the studio from bankruptcy. The film was a huge box-office success, though critics mainly praised its inventive cinematography and Gary Oldman’s performance. A seductive visual experience with operatic scenes where atmosphere matters more than plot. In 1995, it even inspired a parody: Dracula: Dead and Loving It. And how does it find its way into Ruben Brandt, Collector? Through a razor, of course—one from which a ravenous vampire sensually licks the blood. Naturally, it had to be part of Kowalski’s knife collection.