Az elmúlt évszázadban nagy átalakuláson mentek át a cirkuszi állatszámok, mutatva, hogy megváltozott a viszonyulásunk a természethez, az élővilághoz. Míg 100 évvel ezelőtt a rács mögött fásultan heverő vagy a porondon ostorral kordában tartott egzotikus nagyvadak jelentették a legnagyobb érdekességet, ma inkább háziasított állatok végzik lelkesen a mutatványaikat a manézsban: pónilovak, uszkárok, galambok, akár macskák. Sőt, míg a klasszikus cirkusznak mindmáig elmaradhatatlan része az állatszám, az elmúlt évtizedekben kialakult, újcirkusz nevű új irányzatban nem is szerepelnek állatok.

1901-ben az akkor még csak 14 éves Brenner József, aki később Csáth Géza néven ismert író lett, ezt írta a naplójába, amikor Szabadkára érkezett a híres Barnum Cirkusz: „Ma reggel bevonult a vasúti pályaházra a négy külön vonat, 67 vasúti kocsi. […] Alig néhány negyedóra alatt leverték a cölöpöket, és 11 órakor állott a két fő és mellék látványossági sátor. […] Beléptünk a csodaemberek sátrába meg az állatkertbe. Körül igen sok kocsi, bennük állatok a majomtól – a vízilóig.” Ez a naplóbejegyzés is jól mutatja, hogy a cirkuszi látványosságokhoz 100 évvel ezelőtt még hozzátartozott az, hogy rácsos kocsikba zárva egzotikus állatokat mutogattak. Hiszen a legtöbb embernek máshogyan nem volt lehetősége arra, hogy a jól ismert teheneken vagy baromfin túl a távoli tájak állatait is megismerje.

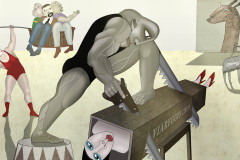

A cirkuszi műsor részét képező állatidomár-számok régebben jelentős részben az állat leigázásáról szóltak. Arról, hogy az ember diadalmaskodik az állat fölött, rákényszeríti az akaratát. De ahogy ma már ízléstelennek tartanánk, hogy törpenövésű embereket vagy szakállas nőket bámuljunk meg egy cirkuszi sátorban (márpedig ilyen is volt), azt is ellenszenvesnek érezzük, ha egy állatot szenvedést okozó vagy méltatlan célokra használnak fel. Az állatvédők is komoly eredményeket értek el ezen a téren, a szabályozás mára sokat szigorodott.

A 21. század cirkuszi világának jobban megfelelnek azok az állatszámok, amelyek az állat és az idomár harmonikus és bizalmi viszonyán alapulnak. A jó idomárok nem ütik, nem sarkantyúzzák az állatukat, hanem suttognak a fülébe, és megismerik a szokásait. Olyan állatfajokkal dolgoznak, amelyek kifejezetten igénylik a tanulást, az aktív munkát. A „vagonállatkertben”, rács mögött mutogatott egzotikus fajok pedig teljesen eltűntek a cirkuszok világából.

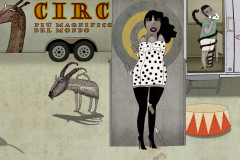

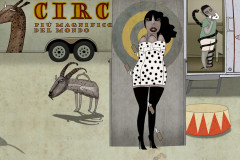

From Cage to Trust: The Changing Role of Animals in the Circus

Over the past century, circus animal acts have undergone a major transformation, reflecting our shifting relationship with nature and the animal world. A hundred years ago, the main attraction was often a bored exotic beast lying behind bars—or being kept in check with a whip in the ring. Today, it’s more common to see domesticated animals performing enthusiastically in the arena: ponies, poodles, doves—even cats. In fact, while traditional circus still relies on animal acts, the modern movement known as new circus—which has emerged in recent decades—features no animals at all.

In 1901, 14-year-old József Brenner, who would later become known as the writer Csáth Géza, recorded the arrival of the famous Barnum Circus in his hometown of Subotica:

“This morning four separate trains arrived at the railway station, with 67 cars. [...] In just a few minutes they had hammered in the stakes, and by 11 o’clock the two main and side attraction tents were standing. [...] We entered the tent of marvels and the zoo. All around were wagons filled with animals, from monkeys to hippos.”

This diary entry vividly illustrates how, a century ago, part of the circus spectacle was simply seeing exotic animals in cages—something most people had no other way of experiencing beyond the familiar cows and chickens of their daily lives.

Historically, animal training acts often centered on domination—on showcasing how humans could subdue animals and impose their will. But just as we would now find it tasteless to gawk at little people or bearded women in a circus tent (which was once common), many people today feel uneasy when animals are used in ways that cause them suffering or indignity. Animal rights advocates have made significant progress, and regulations have become much stricter.

In the 21st-century circus, animal acts that are based on mutual trust and harmony between trainer and animal are much more appropriate. Good trainers don’t hit or spur their animals—they whisper in their ears, get to know their habits, and work with species that naturally enjoy learning and being active. The days of the “traveling zoo” and caged wild animals on display are long gone from the circus world.